13 Oct 2025

Jordi Ma Lu – Architect and Lecturer at University for the Creative Arts, discusses the dilemma of teaching professional practice in a transnational educational setting.

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-10-17-at-19.18.51-copy.jpg)

When adaptation creates confusion

In the 1970s, Chef Peng introduced a dish – General Tso’s Chicken – in his restaurant on East 44th Street in New York City, claiming its roots in Hunanese cuisine. While presented as a Chinese dish, this was no more than an American adaptation of a traditional dish that quickly became popular everywhere but was unknown in China itself.

This contradiction, often shared in gastronomy, can also be extrapolated to transnational education (TNE). In my teaching setting, a Sino-British university based in China, and as a teaching staff member representing the British counterpart, I often found myself constantly adapting the delivery of a body of knowledge that I obtained in Western countries to suit the Chinese context. While this is often referred to as the decolonisation of a curriculum or unlearning of what we have interpellated in the Westernised university, the case that I am exposing here is when adjusting or decolonising doesn’t seem to work well.

In architecture education, regulatory frameworks and project stages are central to our pedagogical delivery, as they support both professional accreditation and design process structure. In the UK, we follow the eight-stage RIBA Plan of Work (2020), a sequence that frames nearly all our teaching, especially within studio projects. However, in China, architectural processes are guided by the GB/T standards, which typically condense these into five stages. Similarly, drawing conventions differ, while British standards (BS 1192:2007 + A2:2016) emphasise standardisation and data integration across BIM environments, Chinese practices follow GB/T 50001 and other national codes, leading to different symbolic representations and layering systems.

This divergence can lead to confusion among students, particularly in a transnational setting where the curriculum is British but the context is Chinese. The QAA Subject Benchmark Statement for Architecture (2020) articulates the need for students to demonstrate an understanding of professional contexts and regulatory frameworks, but does not dictate which national standard should be prioritised. Meanwhile, recent sector discourse, including the QAA’s 2024 Quality Evaluation and Enhancement of TNE review and the 2023-27 strategic outlook, emphasises the importance of cultural contextualisation without compromising educational standards. Therefore, my role becomes one of negotiation – mediating between frameworks while helping students navigate a bilingual architectural literacy.

Binary systems

This reflection comes because of a situation where a student approached me by showing a drawing symbol that she found in her Chinese online manual to check whether the way I asked her to draw in AutoCAD in the previous session was correct, since both symbols were different from each other. It was a clear confrontation between the UK and the Chinese systems. Finding myself suddenly challenged, I tried to figure out whether this Sino-British partnership was aimed at providing a British education in the Chinese context, or whether the aim was to only provide retention and attainment by delivering the courses in English. Without much time to spend, I decided to clarify the different systems and let her choose.

It is widely believed that most of the students will work in design practices in China after university. But this is interestingly contrasted by the fact that their learning is often delivered by foreign teaching staff whose knowledge is better suited to their country of origin, particularly regarding matters that have practical applications, as noted above. If adaptation and decolonisation are often cited as strategies to better integrate transnational education into foreign contexts, their application becomes more complex when professional standards are nationally bounded and non-interchangeable. In this case, merging UK and Chinese systems is not feasible – it becomes a binary choice between frameworks.

To critically consider this, ‘decolonisation’ must be unpacked not simply as diversifying the curriculum, but as challenging epistemic dominance, especially of Eurocentric knowledge structures. However, when regulatory standards, such as drawing codes or planning stages, are rooted in nation-specific legislation and industry practice, the call to decolonise must engage with incompatibility, not just imbalance.

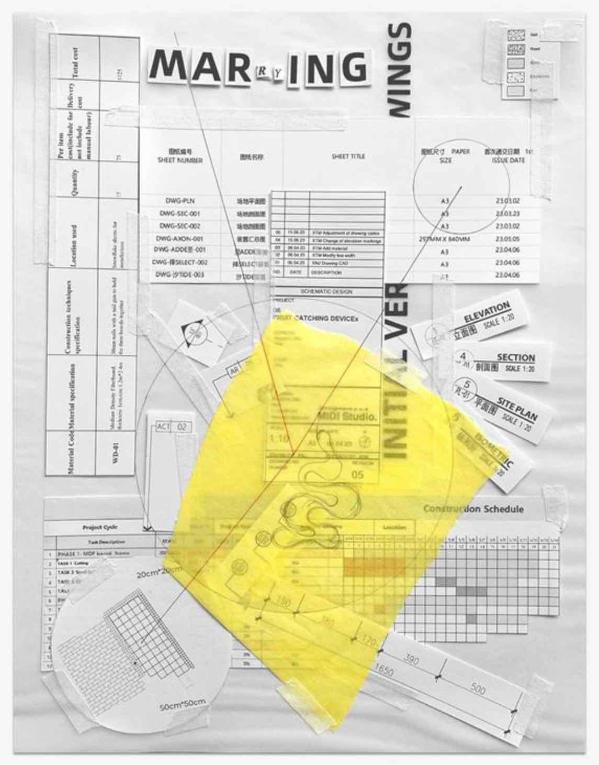

(Collage using cutouts from students’ work to manifest the medley of different languages from involuntary actions, giving birth to a new style.)

Learning two systems in parallel

In Catalonia, a bilingual province of Spain, language subjects in primary and secondary schools are simultaneously delivered with the same content structure for Catalan and Castilian subjects. This translates into learning the same equivalent aspects in each of the languages, doubling the teaching delivery to some extent. While this seems repetitive, the education system ensures that students understand the difference between both languages and equips them with bilingual abilities.

While this approach may seem at odds with transnational education’s aspiration to ‘marry cultures’ into a singular global offering, recognising the autonomy and parallel validity of different systems is crucial. This is especially true in avoiding uncritical westernisation and mitigating confusion in pivotal technical skills such as drawing conventions.

Assessment in the hybrid zone

The dilemma becomes most acute in assessment. For example, when reviewing a student’s Final Major Project that included construction drawings, the jury panel in the defence flagged inconsistencies where students had blended BS 1192 layering conventions with GB/T symbolic logic, producing work that merge both systems and creating a new eclectic style like the ‘General Tso’s Chicken’ dish. This raised questions around marking criteria: do we assess based on UK standards (as benchmarked in the QAA Subject Statement and RIBA Part 1 expectations), or acknowledge a hybridised regional style?

This reflective piece of writing has encouraged me to think about the challenges and priorities of transnational education. Understanding that conflicts between systems exist and blending them sometimes is not an option, particularly when they respond to matters that have a practical application validated by the QAA Subject Benchmark Statements or regulated by professional bodies. Questions such as which side we should prioritise, or whether they should be delivered in parallel, are still pending to answer. If something we can ensure is that the longer time we take to answer, the more confusion we will create among the students, because the emergence of a newly invented language is already a real fact.

You can find a copy of Jordi's article on the Advance He website here.

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-10-17-at-19.18.51-copy-250X250.jpg)