17 Jan 2025

Ever since my days as an academic developer at UCA, I have nurtured an interest in socio-cultural forms of teacher reflection (Loads and Campbell, 2015; Roxa and Martensson, 2009; 2012) which encourage university teachers to continually improve their teaching and learning in conversation with ‘significant others’ (Roxa and Martensson, 2009; 555).

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-01-13-at-11.22.52-copy.jpg)

Ever since my days as an academic developer at UCA, I have nurtured an interest in socio-cultural forms of teacher reflection (Loads and Campbell, 2015; Roxa and Martensson, 2009; 2012) which encourage university teachers to continually improve their teaching and learning in conversation with ‘significant others’ (Roxa and Martensson, 2009; 555). I was a key advocate for the introduction of Peer Supported Review (Gosling and Mason O’Connor, 2009) at UCA in 2012, as a socio-cultural form of teacher reflection, with peers working together as “critical friends” to ‘improve teaching and student learning through dialogue, self and mutual reflection designed to stimulate motivation’ (Gosling, 2009:10). At the time, the scheme was seen as a worthy replacement to the evaluative, graded and deeply unpopular Peer Observation of Teaching (aka POT) scheme. However, I also recognised at the time that the reflective value of engaging in any kind of formal teaching observation can sometimes be lost in the evanescence of competing needs, space and time (Burnard and Hennessey, 2006: piv).

When, it’s not that the whole thing is new, it’s just understanding “oh, all right, okay, there’s something theoretically that supports what I’m doing there.” (Participant E, McKie, 2022)

If staff cannot see the value of reflection, the worry is that the full transformative potential of a Peer Supportive Review can be lost. Without the reflection, what may have originally been framed as a collaborative critical dialogue between two peers may simply become a reductive, form filling exercise. Now, as an Associate Dean Student Experience at London College of Fashion, teaching both staff and students to reflect, I continue to enthuse about the power of reflection to transform teaching and enhance the student experience. As I introduce fashion educator colleagues to various theoretical concepts for reflection, I also encourage dialogue on the connections between reflective theory and academic practice. The rich discussions that follow suggest a keenness to engage with models and frameworks for reflection such as peer supported review, but a hesitancy on how these might be worked into busy teaching routines. One also detects a reluctance around the language of reflective teaching, especially from dual professionals who may not have received formal training in pedagogy.

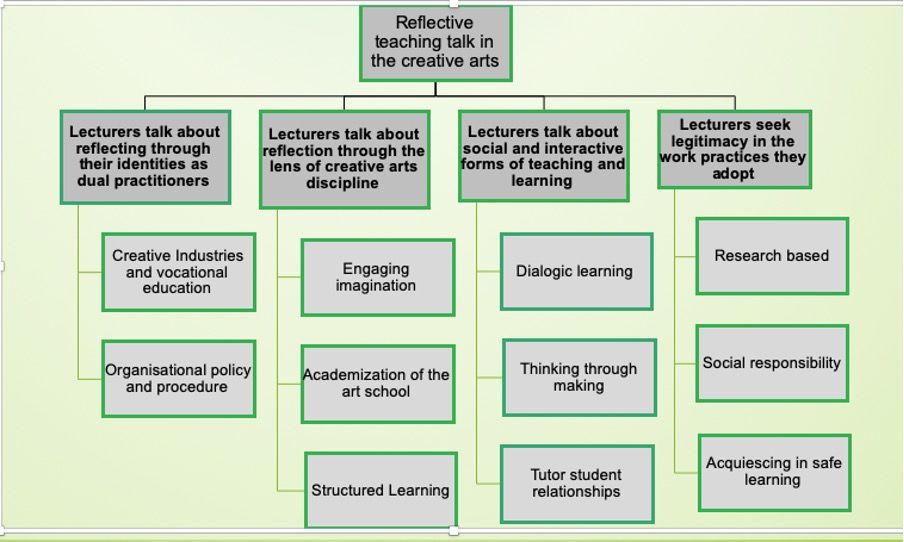

These observations have led me on a quest in my own research to locate more meaningful forms of teacher reflectivity, which encourage creative arts educators to make positive associations, connections and applications through reflective schemas such as Peer Supported Review. This investigation culminated in an EdD research study (An exploration of how creative arts lecturers talk about reflection in their teaching – see Figure 1) to explore the social and cultural components influencing reflection in teaching.

Figure 1: Analysis of reflective teaching talk in the creative arts

It was through my analysis of lecturers’ talk that I gleaned understandings of how we might enable more meaningful reflectivity to develop our teaching and enrich the student experience. My research findings suggest that how creative arts educators talk about reflecting on their teaching might be better understood through their dual identities and disciplinary practices in the creative arts (Drew, 2004; Orr and Shreeve, 2017; Shreeve et al, 2010). The lecturers I interviewed for my study talked about the social and interactive nature of their teaching and learning contexts and their tendencies to contest reflective practices that do not take account of their workplace contexts. My study also highlights the tendency of lecturers to more likely accept as legitimate reflective activities that emerge from everyday work, and which potentially connect with colleagues’ values because they concern teaching practices that make a difference (Loads and Campbell, 2015; Roxa and Martensson, 2009). These insights are encapsulated as a set of ‘Oblique strategies for reflecting on teaching’ (see Table 1 below), with participant quotes, for lecturers and supporters of learning undertaking Peer Supported Review and other forms of professional development in teaching. The strategies provide a means of making positive associations, connections and applications to stimulate reflection on teaching.

| Use your own ideas | |

| ‘And actually, recognising that there are cycles of reflection that are referred to in education that are exactly the same as the cycles of reflection in creative practice and the things that are happening all the time.’ | Apply reflective practices that are personally meaningful and that connect with the realities of your creative educative context. This might include engaging in arts-enriched development activities such as collage, sculpture, poetry, photography and other creative ways of prompting deep thinking about teaching practices and teacher identities (see work by Loads, 2009). |

| State the problem in words as clearly as possible | |

| ‘I am interested in taking the skills I have acquired and putting a pedagogic vent on those so that I can pass across a particular way of thinking about the medium in the context of UG teaching’ (Participant A, McKie, 2022) |

|

| Work at a different speed | |

| ‘I have to say I love all that introducing educational ideas to improve teaching. My own research let’s say leads me to those places often. You know, it has adjusted my own teaching as I have become more experienced…’ | Put your teaching into slow motion to locate previously unconscious material or see familiar aspects in fresh ways. For example, you might consider engaging in a teaching observation with an academic colleague outside of your discipline or working with a librarian or technician. |

| Turn it upside down | |

| ‘What I am trying to do I think is to somehow engage students in fundamental ways of thinking that are transferable to different toolsets and environments and which are disruptive in the sense it will change the way they think about the medium they are working with.’ | Disrupt reflection on your educational practices by thinking about it as a provocation, a story, poem or a metaphor. Narrative techniques to help you do this could include the use of free writing, writing a postcard to self, or telling the story through your students’ viewpoints. |

| Don’t avoid what is easy | |

| ‘You create a sandbox where everything is up for grabs in some ways. Everything is possible. And it's easy to reset’. | Set up safe spaces to deconstruct teaching terms, experiment with educative technology and “un-learn” practices. These might include setting up a ‘sandpit’ to play with pedagogy or creating a ‘what if’ forum to discuss links between disciplinary practice and inclusive pedagogy. |

| Use an old idea | |

| ‘There’s lots of different teaching strategies that we would employ to engage students. So, instead of just focusing on a lecture, it’s much more that thing of dialogue and exchange of ideas really…’ | Locate an idea from your disciplinary or professional practice to put a fresh perspective on your reflection as an educator. Your discipline, for example, may be more receptive to radical pedagogies, which embrace social justice or social purpose, and which by nature are more dialogic and interrogative. |

Table 1: Oblique Strategies for reflecting on teaching

References

- Burnard, P. and Hennessey, S. eds. (2006) Reflective practices in arts education (Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics and Education). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Drew, L. (2004) The Experience of Teaching Creative Practices: Conceptions and Approaches to Teaching in the Community of Practice Dimension in 2nd CLTAD International Conference, Enhancing Curricula: The Scholarship of Learning and Teaching in Art and Design, April 2004, Barcelona. Available at: https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/644/

- Gosling, D. and Mason O’Connor, K. (2009) Beyond the Peer Observation of Teaching, SEDA Paper 124

- Loads, D. (2009) Rich Pickings: Creative Professional Development Activities for University Lecturers. Leiden: Brill Sense.

- Loads, D. and Campbell, F. (2015) Fresh thinking about academic development: authentic, transformative, disruptive? International Journal for Academic Development, 20 (4), pp. 355-369.

- McKie, A. (2019) ‘Reflective teaching in the creative arts.’ Journal of Useful Investigations in Creative Education, https://juice-journal.com/2019/05/21/reflective-teaching-in-the-creative-arts/

- McKie, A. (2022) An exploration of how creative arts lecturers talk about reflecting on their teaching EdD Thesis. University of Roehampton: https://pure.roehampton.ac.uk/portal/en/studentTheses/an-exploration-of-how-creative-arts-lecturers-in-higher-education

- Orr, S. and Shreeve, A. (2017) Art and Design Pedagogy in the Creative Curriculum. London: Routledge.

- Roxa, T. and Martensson, K. (2009) ‘Teaching and learning regimes from within: Significant networks as a locus for the social construction of teaching and learning’, in: Kreber, C. (ed.) (2009) The university and its disciplines: Teaching and learning within and beyond disciplinary boundaries. London and New York: Routledge.

- Shreeve, A., Simms, E. and Trowler, P. (2010) A Kind of Exchange: Learning from Art and Design Teaching, Journal of Higher Education Research and Development, 29 (2), pp. 125-138.

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Reflection--1000X1500.jpg)