Handbooks and Unit Briefs

These are sometimes visually and linguistically complex, open to misinterpretation and stress/anxiety; reading heavy; centred on a white western core culture.

They may not support the needs of those with learning difficulties (SpLDs), international students (IS) or widening participation (WP) students.

Simplify.

- Consider words that might have culturally diverse meanings; either replace or include in a glossary. You may find ‘The A to Z of Alternative Words’ guide useful (www.plainenglish.co.uk).

- Design against the British Dyslexia Association style guide (www.bdadyslexia.org.uk).

- Place text near relevant pictures or diagrams.

- Check ‘readability’ score (https://readability-score.com).

- Check that the reading list is (a) graded for importance, (b) key chapters are indicated, (c) as many texts as possible can be read on line.

- Consider alternatives to reading, e.g. online resources including film and video.

- Check images and texts are culturally diverse, e.g. are LGBTQ+ people, a range of ages and global cultures represented? It may be useful to think about the nine protected characteristics of the Equality Act (2010).

- Use tinted paper. (Cream, buff, grey are recommended.)

Lesson Planning

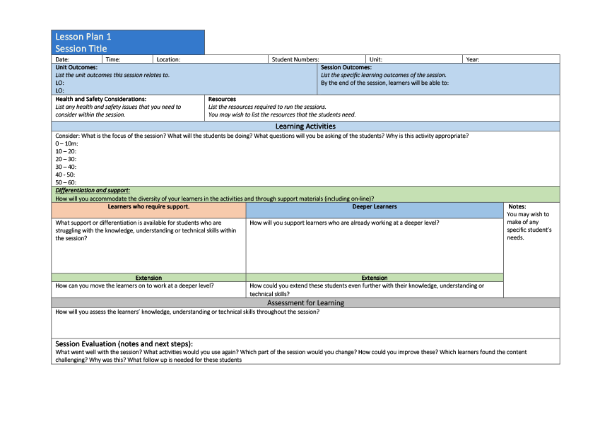

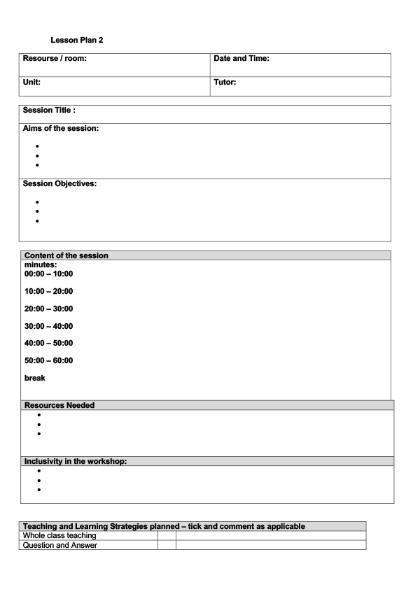

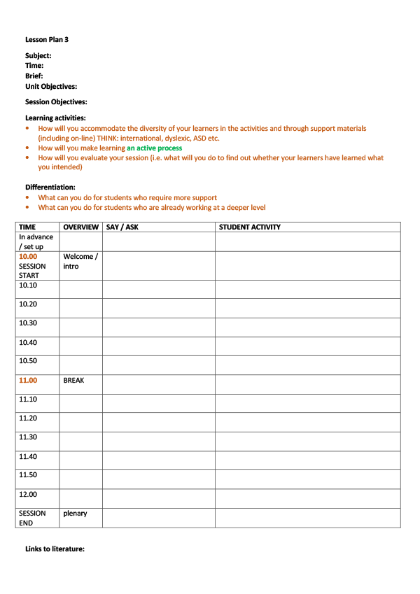

Lesson plans are such a useful tool for us as teachers. They help us to marshal our thoughts, manage time more effectively in sessions, and ensure that important parts, such as recaps and plenaries, are included.

We can plan how to scaffold differentiated learning, making our delivery more inclusive, and constructively align our teaching content with the learning objectives of the session and the unit of learning. With a plan in place, we can keep on track to facilitate students’ learning in the most effective way.

What should a lesson plan include?

- Lesson Title: The session title

- Basic practical information such as Date / Time / Location / Student Numbers / Unit / Year or level of students

- Any health and safety considerations

- What resources do you need, what resources will your students need?

- Unit objectives – what larger unit of learning is the session contributing to? What are the unit’s learning objectives?

- What are the session’s learning objectives? These may be pre-determined, but if you are writing these yourself, session learning objectives are often written to follow the phrase: By the end of the session, learners will be able to...

By specifying the learning objectives in a plan, we can remind ourselves what we need to do to help students successfully pass the unit and the course.

- Introduction. Is there material you need to recap from previous sessions? This is also the time to share the session LOs with the students, so that they know what to expect. This is best inclusive practice.

- Learning activities. What is the focus of the session? What will the students be doing? What questions will you be asking of the students? How active and engaging is the learning?

In this part, it can be helpful to break up your session into 10 minute sections, and plan what you are doing during the time. Also ask yourself - what are the students doing in each of those 10 minutes? If the answer to that is sitting and listening, this is a strong clue that you need to add more activity into your session.

Working out in advance how you will spend the time, can help you manage the time during a session more effectively, ensuring you cover all the necessary material.

- Differentiation and support. How will you accommodate the diversity of your learners in the activities and through support materials? This part of a session plan helps to ensure that we make our teaching as inclusive as possible, by working out in advance what we will do for students who require more support, and for students who are working at a deeper level and may need extension activities. Do you have students who have declared specific learning needs? How will you accommodate them?

- Assessment for Learning. How will you assess the learners’ knowledge, understanding or technical skills throughout the session? This could be informal formative assessment and feedback, or summative – at the end of a unit of learning.

- Recap / plenary / evaluation for students. It is always effective to remind students of what they have learnt during the session. You can also remind them of upcoming tasks and deadlines. By putting this in a plan, you can ensure that you don’t overlook this important stage.

- Lesson Evaluation – for you as the educator. What went well with the session? What activities would you use again? Which part of the session would you change? How could you improve these? Which learners found the content challenging? Why was this? What follow up is needed for these students?

Assessment

UCA Glossary of Assessment Terms

- Unit: Self-contained elements of study with defined learning objectives, contributing to a course.

- Assessment Component: Activities undertaken by students to assess the extent to which learning objectives of a unit are met.

- Assessment Criteria: Descriptions of what a student is expected to do to demonstrate that learning outcomes have been achieved.

- Credit / Credit Volume: Numerical value denoting the amount of learning expected for a student to achieve the outcomes of a unit.

- Credit Level: Reflects the depth of learning and intellectual demand required to meet the learning outcomes.

- Resit: Opportunity for reassessment without attendance, usually completed before the start of the next academic year.

- Defer: Postponing an assessment attempt due to mitigating circumstances, allowing assessment as if for the first time.

- Enrol/Register: Processes of joining a course (enrol) and a unit (register) at UCA.

- Retake: Reassessment of an entire unit with attendance in the following academic year, including previously passed components.

- Progression: Movement from one stage to the next in a course, subject to meeting credit requirements.

- Stage: The period of study leading to a formal progression or award point.

- Moderation: A quality assurance process where a sample of student work is reviewed to ensure consistency and fairness in marking and grading practices across different assessors and units.

- Sampling: The selection of a representative subset of student work from a larger cohort for the purpose of moderation or validation, ensuring the assessment process's integrity and consistency.

- Internal Verification: A quality assurance process used at UCA to ensure the reliability and consistency of assessment decisions within the university. This process involves a thorough review of assessment tasks, marking schemes, and the grading of student work by internal staff members. The purpose is to confirm that assessment criteria are applied consistently in the marking of students work, and that the assessment process is fair, valid, and aligned with UCA's academic standards. Internal verification may involve blind double marking, sample marking, cross-marking or moderation [see the level 7 CCF/Taught Course Regulations for more details].

- External Verification: A process involving external experts reviewing the assessment and verification procedures on a course to ensure they align with external standards and requirements. This process typically includes the examination of a sample of student work, assessment tasks, and verification records. External verifiers, who are professionals or academics from other institutions or relevant industries, provide an objective assessment of whether UCA's internal verification and overall assessment practices meet the expected criteria of external accreditation bodies, industry standards, or national educational benchmarks.

- Learning Objective: A specific, measurable statement detailing the desired outcome of student learning for a unit or course, guiding the design of curriculum and assessments at UCA.

- Mitigating Circumstances: Factors outside of a student's control that may negatively impact their performance in assessments, considered by UCA when reviewing assessment results.

Formative assessment strategies

Writing effective feedback:

- motivates, encourages and challenges students.

- uses a positive emotional tone to encourage students and increase their ‘self-efficacy’ – their belief that they are capable of doing well. Negative and personally critical comments are ineffective and damaging.

- clearly explains why a student received the mark that they did according to the assessment criteria

- encourages active learning strategies – i.e. explains what a student could do to improve further

- is constructive in that it explains what the student could do next time to avoid a mistake or to improve their work helps students reflect on their own progress and develop skills of self-evaluation

- guides students to additional resources or learning activities that could help them

- helps students to feel a sense of accomplishment.

- makes it clear to students what the educational goals of the course are, for example whether greater emphasis is placed on familiarity with the literature or on competence. Students should be able to see how marks are arrived at in relation to the criteria, so as to understand the criteria better in future. They should be able to understand why the grade they got is not lower or higher than it actually is. One way to do this is to use the sentence stems: “You received a better grade than you might have done because you…” and “To have got one grade higher you would have had to …”.

- Reactivates or consolidates prerequisite skills or knowledge prior to introducing the new material.

Feedback tips:

- Make sure your feedback is written against the assessment criteria for a unit.

- Feedback is ‘for’ learning and should therefore be constructive, highlighting how the student could improve upon their grade.

- Avoid writing things like ‘I am very pleased to see you working hard…’ Feedback is about the student, it’s not about you!

- Keep your feedback clear, concise, and objective, but do make sure you refer to the student’s work so that they know it is all about them.

- Make sure you use adjectives from the relevant grading descriptors (e.g. good, very good) to indicate the level of achievement. But take care not to be formulaic.

- Avoid using language that might be too open to interpretation.

Considerations to help your course improve feedback:

- To enable good feedback, assessment criteria need to be clearly written and unambiguous. Consider using minor course modifications to improve some of the assessment criteria.

- When a brief is being set, include an exercise to help students understand and apply assessment criteria. This can help them become familiar with the language and terminology used in assessment and feedback. An exercise could involve looking at previously assessed work and asking them to apply the assessment criteria to it. Another exercise might be to introduce a peer assessment exercise further into the brief in which students assess each other’s work. This can be supported by information in the course handbook.

- Rather than just focusing on ‘feedback’ to students (which invites a student dependency on the tutor), consider introducing the idea of ‘feeding forward’, so that students take more of an active role in tutorials. Encourage students to ask questions of the tutors to help them ascertain what they need to improve and how to go about it.

- Explain to students that their work will be marked fairly using internal verification processes such as 2nd marking.

- Explore ways to achieve greater attendance at tutorials and student ownership of feedback. For example, you could design a feedback tutorial form that requires students to prepare some questions before a tutorial, or develop guidance for students on how to get more out of their tutorial or crit.

- Consider alternative ways of providing feedback to reduce students’ dependency on ‘official’ feedback channels such as the written feedback form. This can also ease the burden of writing feedback. For example, consider

- creating more peer assessment points where students assess each other’s work in a ‘mock crit’ using ‘critical questioning’ and assess against the grading descriptor

- Tools like Turnitin or Blackboard (myUCA) can provide quick, efficient, and detailed feedback.

- Instead of traditional written feedback, instructors can record their comments. This approach can be more personal and nuanced, allowing students to hear tone and emphasis, which can be lost in written communication.

- Encourage students to self-assess their work against provided rubrics or criteria before submitting. This process helps students to understand the expectations better and internalise the assessment criteria, making the feedback they receive more meaningful and actionable.

Inclusive formative assessment

- Don't assume students' backgrounds, abilities, or preexisting knowledge. Create opportunities to understand your students and reflect on any assumptions you may hold (Borkin, 2020;Ambrose et al., 2010; Hockings et al., 2008).

- Clearly articulate course aims, objectives, expectations, and assessment criteria. This helps students understand and prioritise their work (Biggs and Tang, 2011; Ambrose et al., 2010).

- Ensure students feel recognised as individuals, avoiding extremes of ignoring or singling out students, particularly those from underrepresented groups (Ambrose et al., 2010).

- Create a positive classroom climate through rapport-building, and a sense of authenticity, which may lead to increased student motivation and engagement (hooks, 1994; Ellis, 2004).

- Understand students' strengths and weaknesses to appropriately challenge them, motivating their engagement (Ambrose et al., 2010).

- Cater to different needs and experiences of students by employing various formative assessment methods, such as portfolio assessment, reflective journals, oral presentations and project-based assessments (Baughan, 2020; Brown and Glasner, 2013; Cast, 2023).

Common problems with feedback

- feedback may come too late to be acted on by students

- feedback may be backward-looking – addressing issues associated with material that will not be studied again, rather than forward-looking and addressing the next study activities or assignments

- feedback may be unrealistic or unspecific in its aspirations for student effort (e.g. “read the literature” rather than “for the opposite view, see Smith Chapter 2 pages 24-29”)

- feedback may ask the student to do something they do not know how to do (e.g. “express yourself more clearly”)

- feedback may be context-specific and only apply to the particular assignment rather than concerning generic issues such as study skills or approaches that generalise across assignments

Self and Peer Assessment

Self Assessment

Self assessment activities provide opportunities for students to evaluate their own progress. A key aspect of a university degree is that it enables students to become independent learners who are able to their strengths and weaknesses and manage their own development needs.

Every course at UCA requires students to engage in what is called ‘independent study’. However, students are not always clear what this means or how to go about it. Self assessment activities provide a clear framework to support and guide students in their independent study and help them take control of their personal development.

Building Self-Assessment into your teaching and learning practice

- Recognise that becoming proficient in self-assessment is a progressive journey, expected to be refined by the conclusion of their undergraduate studies.

- Tailor self-assessment tasks to various experience levels, offering more support for those newer to this practice. Clearly communicate the purpose and benefits of self-assessment to students, dispelling any misconceptions.

- Provide structured criteria for students to evaluate their work such as the grading descriptors and learning objectives of the units.

- Guide students in developing a meta-awareness of their assessment abilities. Encourage them to articulate and critique their work, and integrate peer assessment for a broader perspective.

Practical Applications at UCA:

- Introduce self-assessment in group projects and class participation, reinforcing fairness and student engagement.

- Utilise reflective journals to offer insights into students' learning processes, even for theoretical components.

- Integrate self-assessment into various assignments, guiding students with specific questions to reflect on their work.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is the process of students grading and/or giving feedback on one another’s work. When introducing peer assessment into your programme, consider introducing this in low-stakes environments by encouraging group marking of previous assignments. Students should be provided with the grading criteria and learning objectives for this activity. Involving students in these activities are a beneficial way to develop their understanding of their assessment criteria and expectations on the unit.

When engaging your students with peer assessment, consider the following:

- Send all materials in advance, including the sample work with structured feedback forms and guidance.

- Whenever feasible, anonymise all submissions to maintain impartiality.

- Consider organising a briefing session along with a rehearsal marking session in groups.

Further resources:

- Boud, D. (1992). The use of self-assessment schedules in negotiated learning. Studies in Higher Education,17(2), 185-201.

- Carnell, B. 2015. Aiming for autonomy: Formative peer assessment in a final-year undergraduate course. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education.

- Falchikov, N. and J. Goldfinch. 2000. Student peer assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis comparing peer and teacher marks. Review of Educational Research 70 (3): 287–322.

- Kearney, S. (2019). Transforming the first-year experience through self and peer assessment. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 16(5). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.16.5.3

- McConlogue, T. 2014 Making judgements: investigating the process of composing and receiving peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education. 40 (9): 1495-1506.

- McDonald, B. & Boud, D. (2003). The impact of self-assessment on achievement: The effects of self-assessment training on performance in external examinations. Assessment in Education, 10(2), 209-220.

- Nulty, D.D. (2010). Peer and self assessment in the first year of university. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 1469–297X.

At UCA we view assessment as a holistic process that extends beyond measuring academic progress to nurturing creative practice, innovation and experimentation, research and analysis and communication and connectivity within create communities. Embedded through these principles is an unwavering commitment to continually improve the way we enhance diversity and inclusivity within our assessment framework. UCA’s assessments are transparent, equitable, and supportive, providing students with valuable feedback to encourage continuous improvement.

Assessment Policy The Assessment Policy 2022/23 document outlines the university's approach to student assessments, covering principles of assessment, assurance of academic standards, conduct of assessments, grading, feedback mechanisms, and the security of assessment information. Additionally, it includes specific guidelines on various assessment methods, including portfolio assessments, and addresses requirements for courses linked with professional or statutory bodies.

Feedback forms

This cover sheet must be completed and submitted with all work including essays, Dissertations and practical work (with the exception of oral assessments).

Students must receive a separate Assessment Feedback Form for each assessment component of each unit. Completed Assessment Feedback forms must be returned to students along with their work within four weeks of the final submission deadline for that assessment component, with the exception of:

- dissertation units: feedback must be provided within eight weeks of the submission deadline; and

- approved late submission (see the Mitigating Circumstances Regulations and the Procedure for Making Adjustments to Assessment Tasks): assessment feedback deadlines will be adjusted to relate to the new submission deadline.

Academic Framework for levels 3,4 and 5

Grading Descriptors

The UCA Grading Descriptors provide a structured and detailed framework to assess student work, ensuring consistency and fairness in grading across all courses at UCA.

- Students can use these descriptors to self-assess their work and understand areas for improvement.

- They can be a guide for setting academic and professional goals throughout the course.

- Helps students understand the feedback from tutors in the context of these descriptors.

- Students and tutors can use these descriptors to track progress over time, ensuring that all essential skills and knowledge areas are being developed.

Academic Framework for Level 7

- The UCA Level 7 Common Credit Framework (CCF) is a set of regulations that apply to taught courses leading to postgraduate awards at UCA.

- The document covers course award alignment, information on units, credits, course stages, assessment and progression.

- You may use the CCF to:

- understand the course structure, including credit levels, volumes, and the framework for higher education qualifications.

- ensure your course content, including core and elective units, aligns with the CCF requirements, reflecting the depth of learning and intellectual demand expected at Level 7.

- assist students in selecting units that align with their academic and career goals, considering the balance between core and elective units.

- inform students about the deadlines for unit selections and the conditions under which changes can be made.

- develop and design assessments according to the CCF, ensuring they accurately reflect the unit's learning outcomes and the required level of intellectual rigor.

- clearly communicate the assessment criteria and weightings to students, helping them understand how they will be evaluated.

- consider grading standards to mark student work. For Level 7, the pass mark is 50, and assessments should be graded between 0 and 100.

- guide students on how to accumulate the required credits for their degree or award and inform them about any additional specifications they must meet.

- understand the implications and mechanisms for internal and external quality assurance.

- The Level 7 Grading Descriptors provide a structured and detailed framework to assess student work, ensuring consistency and fairness in grading across all courses at UCA.

- Students can use these descriptors to self-assess their work and understand areas for improvement.

- They can be a guide for setting academic and professional goals throughout the course.

- Helps students understand the feedback from tutors in the context of these descriptors.

- Students and tutors can use these descriptors to track progress over time, ensuring that all essential skills and knowledge areas are being developed.

Further information

- For further information on Collaborative Partners and the Institute for Creativity and Innovation (ICI) see here.

Common Problems with Summative Assessment

- You must assess the learning that has taken place – not the student. Your personal views about a particular student should not enter in to the assessment process, your focus should be solely on assessing the learning that they have demonstrated through the work they have produced.

- You can only assess things such as attendance, timekeeping, effort if they have been clearly specified in the Learning Outcomes and Assessment Criteria. For example, if you want to assess students on attendance this must be clearly stated in the learning objectives.

- You should be using the assessment criteria to assess the learning that has been demonstrated through the work – this is called ‘criterion referencing’. You are not supposed to compare one person’s work with another – this is ‘norm referencing’.

- You are assessing against the criteria and not against individual progress made. You can mention how much a student has progressed in your feedback, but you must assess their learning and not their progress.

- You mustn’t assess effort. A student may have put in a huge amount of effort, but you must assess what they have learned and not the effort they have put in.

Inclusive summative assessment

Below are several evidence-based strategies for making summative assessments more inclusive:

- Clearly defined assessment criteria and rubrics support fairness and transparency for students, ensuring assessment is consistent and unbiased Biggs and Tang (2011).

- See the UCA generic grading criteria.

- Offering a variety and flexibility of assessment formats such as presentations, portfolios and project-based learning help cater for diverse learning needs, aligning with the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) as advocated by Rose and Meyer (2006).

- Instead of group presentations, consider remote presentations via Zoom/teams.

- Consider getting students to create a video podcast of their practice, demonstrating their technical skills and developments. Incorporating authentic assessment tasks that reflect real-world applications of knowledge and skills can enhance inclusivity as they tap into meaningful, real-life contexts (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005).

- Ensure assessment materials and questions use inclusive language and diverse examples to avoid bias.

- See the QAAs toolkit for making the language of assessment inclusive for further details. There are some great reflective prompts here to consider when building your assessment tasks.

- Provide timely and constructive feedback that focuses on improvement rather than just grades (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

- Incorporate peer and self-assessment to promote self-regulation and peer learning. See [link] for further information on peer and self-assessment.

- Involve students in the assessment design process to ensure their perspectives and needs are considered (Bovill et al., 2011; Bain, 2010).

Create flexible alternative assessments, providing choices that are of equal importance and continue to meet the same criteria for research, analysis and communication as traditional modes, e.g. blogs, magazines, television.

Ensure the topics are culturally diverse.

Demonstrate characteristics of good assignments using examples; explain plagiarism.

Traditional modes of assessment unfairly discriminate against SpLD, IS and WP students.

Ensure students know how their work will be assessed.

The purpose of assessment is to assess the learning not that the students can write.

Feedback

Research (e.g. Lizzio and Wilson, 2008; Poulos and Mahony, 2008; Walker, 2009; Weaver, 2006) suggests that written feedback comments should be:

|

Understandable |

Is it expressed in a language that students will understand? |

Yes/No |

|

Selective |

Try to include 2/3 things that the student can improve upon. |

Yes/No |

|

Specific |

Do your comments relate to specific instances in the student’s submission? |

Yes/No |

|

Timely |

Are your comments provided in time to improve the next assignment? |

Yes/No |

|

Contextualised |

Are your comments framed with reference to the unit and the learning outcomes? |

Yes/No |

|

Non-judgemental |

Focused on assessment criteria, marking descriptors? |

Yes/No |

|

Balanced |

Pointing out the positive as well as areas in need of improvement? |

Yes/No |

|

Forward-looking |

Do you suggest how students might improve future assignments? |

Yes/No |

|

Transferable |

Are your comments focused on processes, skills, i.e. not just on knowledge content? |

Yes/No |

|

Personalised |

Are your comments specific to the student? |

Yes/No |

Adapted from: Nicol, D (2010) ‘From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education’ In: Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 35:5, pp.501-517

Workshop Practice

Short for ‘critique’: “to evaluate (a theory or practice) in a detailed and analytical way.” (Oxford Languages.com)

Also described as group crits, where students share their work publicly with their peers and tutors. Crits are a workshop practice often used in creative arts subjects.

Crits serve several important roles:

- Feedback and Evaluation:

Provide a platform for students to present their work, and for tutors and peers to offer feedback

Crits can be used to give formative feedback – assessment for learning, that ‘informs’ students’ future steps, and summative feedback – assessment of learning, that ‘summarises’ students’ learning.

- Peer Learning and Collaboration:

Foster a collaborative and interactive learning environment among students.

Build a sense of community through open dialogue and practical sharing of experiences.

Encourage peer-to-peer discussions and the exchange of ideas.

Expose students to a variety of approaches through the analysis of their peers' work.

- Communication Skills:

Help students develop the ability to give and receive constructive criticism.

Improve communication skills by articulating thoughts and insights about their own work and the work of others.

- Critical Thinking, Analysis:

Encourage students to think critically about their artistic choices and the conceptual underpinnings of their work.

Enhance analytical skills as students evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their peers' projects.

- Reflection and Revision:

Facilitate a reflective process for students to reconsider and refine their artistic concepts and approaches.

Encourage iterative development by providing opportunities for students to implement feedback in subsequent iterations of their projects.

- Preparation for Professional Practice:

Model the critique process found in professional practices and prepare students for the realities of presenting and defending their work.

Foster a resilient attitude towards criticism, helping students develop the ability to navigate feedback in their future careers.

Downsides to relying on crits:

- Ineffective Feedback:

Crit feedback, particularly peers’ crit feedback, doesn’t always align with learning objectives, and may be unhelpful.

Different participants may offer conflicting feedback, leaving students uncertain about the direction they should take in their work.

Time constraints in group crits may limit the depth of analysis and discussion for each student's work, leading to superficial feedback.

Individual artistic challenges or technical issues may not receive adequate feedback in a group setting, hindering targeted problem-solving.

- Social Pressure and Anxiety:

Some students may feel anxious or pressured in a group setting, inhibiting their ability to express themselves or hindering their openness to feedback. International and neurodiverse students may be particularly vulnerable.

In cases where the critique becomes overly critical or competitive, it can create a negative atmosphere that discourages creativity and risk-taking.

Some students may be uncomfortable sharing their work in a public setting, inhibiting their willingness to take risks and experiment with new ideas.

Certain voices may dominate discussions, suppressing the contributions of others.

- Overemphasis on Final Products:

Group crits may focus excessively on the final outcomes, overlooking the importance of the artistic process and experimentation.

An emphasis on industry practice isn’t always appropriate or suitable, particularly for younger students.

To mitigate these downsides, it is essential to carefully structure crit sessions, encouraging a supportive and inclusive atmosphere, and providing guidance to students on effective crit techniques. Additionally, incorporating individual tutorials, peer reviews, and self-reflection alongside group crits can offer a more well-rounded and inclusive workshop experience for students.

Further reading

Advance, H. E. (2014) The perception and interpretation of formative assessment and feedback in art and design. At: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/perception-and-interpretation-formative-assessment-and-feedback-art-and-design (Accessed 13/12/2022).

Blair, B. (2006) '‘At the end of a huge crit in the summer, it was “crap” – I’d worked really hard but all she said was “fine” and I was gutted.’' In: Volume 5 Number 2. Article. English language. At: https://intellectdiscover-com.ucreative.idm.oclc.org/content/journals/10.1386/adch.5.2.83_1

Cennamo, K. and Brandt, C. (2012) 'The ‘right kind of telling’: knowledge building in the academic design studio' In: Educational technology research and development: ETR & D 60 (5) pp.839–858.

Pollock, V. L., Alden, S., Jones, C. and Wilkinson, B. (2015) 'Open Studios is the beginning of a conversation: Creating critical and reflective learners through innovative feedback and assessment in Fine Art' In: Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education 14 (1) pp.39–56.

Shreeve, A., Sims, E. A. R. and Trowler, P. (2010) '‘A kind of exchange’: learning from art and design teaching' At: https://www-tandfonline-com.ucreative.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1080/07294360903384269

Awarding Gaps

The term "awarding gap" in the context of UK higher education refers to disparities in academic outcomes between different groups of students. Specifically, it focuses on differences in degree attainment, classifications, and honours achieved by students from various demographic backgrounds, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and disability.

The awarding gap is a subset of the broader issue of educational attainment gaps, reflecting disparities in success rates at the end of a course of study. The concern arises when there are noticeable differences in the proportion of students from different demographic groups who achieve the highest degree classifications (e.g., first-class honours or upper-second-class honours).

You can find more information on awarding gaps here:

Office for Students (OfS)

Since January 2022, the OfS in the UK has been actively engaged in addressing issues related to awarding gaps and promoting equality in higher education. The OfS is responsible for regulating and overseeing higher education providers in England. It places a strong emphasis on ensuring that all students, regardless of their background, have equal opportunities for success and are not disadvantaged by systemic barriers.

The OfS has set expectations for higher education providers to actively address and eliminate disparities in degree outcomes. They have encouraged institutions to take a data-driven approach to identify and understand awarding gaps, considering factors such as ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic background, and disability.

Degree-awarding gaps: a targeted approach by OfS

OfS Access and participation data dashboard

OfS Degree attainment resources

OfS’s case studies on effective practice in access and participation

Blake, J. (2022) Next Steps in Access and Participation at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/next-steps-in-access-and-participation/ (accessed 1 Sept. 2022)

Centre for Transforming Access and Student Outcomes in Higher Education - CAST is an organisation that undertakes and uses research and evaluation to determine what works in eliminating equality gaps in higher education.

Kingston University inclusive curriculum consultation programme

QAA

Eliminating differential outcomes and closing racialised awarding gaps - online repository

Time Higher Education – three immediate changes academics can make to close awarding gaps

AdvanceHE

AdvanceHE Degree Attainment Gaps

AdvanceHE launches ethnicity awarding gaps in UK HE in 2019/2020 report

UCA

UCA Transparency Information 2021/2022

UCA's Saturday Clubs are led by experienced creative practitioners. They give you a chance to develop a portfolio of work. The programmes equip you with new skills to help build your confidence and ability to express your ideas and hone your creative practice.

All our Saturday clubs are free to participate in and materials are provided to anyone allocated a place. You must be a UK resident to take part.

UCA's Saturday Clubs are led by experienced creative practitioners. They give you a chance to develop a portfolio of work. The programmes equip you with new skills to help build your confidence and ability to express your ideas and hone your creative practice.

All our Saturday clubs are free to participate in and materials are provided to anyone allocated a place. You must be a UK resident to take part.

Using Digital Technologies

Phase 1: Introduction of Ultra Base Navigation - August 1, 2023

In August 2023, myUCA transitioned to Blackboard Ultra Base Navigation, an updated version of the Blackboard learning management system (LMS). This upgrade aimed to enhance user interface and functionality of myUCA, making it more user-friendly and accessible.

Phase 2: Transition to Ultra Courses for Early Adopters - September 2023

Starting in September 2023, we will begin the gradual process of upgrading courses to the Ultra Course View. This phase will involve collaborating with you to prepare for the transition. By the academic year 2024/2025, all new courses will be using the Ultra course interface, offering an enhanced learning and teaching experience.

Please find below information about both Ultra and Blackboard courses

- My UCA Ultra - Early Adopters of Ultra Courses

- Announcements

- Adding a Banner

- Adding Discussions

- Progress Tracking

- Course/ Unit Calendar

- Course Activity Report

- Adding Content

- Learning Modules

- Release Content

- Create Student Groups

- Adding a Journal

- Grading a Journal

- Adding Turnitin Assignments

- Editing a Turnitin Assignment

- Viewing Group Assignments in Turnitin

- Grading Turnitin Assignments

- Adding Blackboard Assignments

- Grading Blackboard Assignments

- Create Group Assignments

- Grading Group Assignments

- Create a gradable test or MCQ

- Grading a test or MCQ

- Student Overview

- Emailing through MyUCA

- Ultra Ally Accesibility Checker

- Ways to interact with students

- MyUCA Blackboard Courses

Panopto is an online video platform widely used in higher education and is the default tool in myUCA to facilitate video recording, live streaming, sharing and content management for students. Panopto can be used to enhance the accessibility and inclusivity of your sessions by providing lecture capture or enhance your learning and teaching by implementing a flipped learning approach by providing asynchronous materials to be reviewed prior to live (synchronous) sessions.

Turnitin is an online tool designed to check originality of written work and mitigate plagiarism. It compares submitted documents against an extensive database of academic papers, websites, and other publications to identify similarities. Turnitin is primarily used to ensure the integrity of academic work.

- Miro

- Miro is an online collaborative whiteboarding platform. It's ideal for brainstorming, mind mapping, and project planning in creative courses. Students and educators can collaborate in real-time, making it excellent for distance learning and group projects.

- View Lecturer Xinya You’s webinar on using Miro in creative education. [link here]

- Padlet

- Padlet is a versatile digital canvas that can be used for creating boards, documents, and webpages. It's useful for organising resources, facilitating discussions, and showcasing student portfolios in creative subjects.

- Mentimeter

- Mentimeter is an interactive presentation software. It's useful for engaging students in real-time during lectures through quizzes, polls, and Q&A sessions, fostering interactive learning and feedback.

- Slido

- Slido is an audience interaction tool that enhances communication between students and educators. It allows for live Q&As, polls, and feedback during classes, ideal for large lecture courses or online learning.

- Canva

- Canva is a design platform that's user-friendly and great for creating visual content. It's useful for students in marketing, graphic design, and digital media for creating presentations, posters, and social media content. It can be a great tool for creating infographics for your students.

- Trello

- Trello is a collaboration tool that organises projects into boards. It is great for project management in group assignments, allowing students to track progress and coordinate tasks.

Computers, digital devices and the Internet offer many ways to make your teaching and supporting learning practice more inclusive. However, it is important to bear in mind that these technologies can also create additional barriers to learning. It is therefore important to make conscious, informed decisions regarding the use of any digital technology with your students.

Pre-session Action.

First, ask yourself whether it is really necessary to use digital technology to accomplish a task. If you or your students can complete the task without using digital technology then give all students the option, as this will remove potential barriers to learning.

If you do want to use technology, ask yourself what aspect of students’ learning you are attempting to enhance and identify appropriate technologies. For example:

Presenting information: you might use PowerPoint, Prezi (for interactive ‘journeys’), Panopto (multi-screen video), images, audio, web pages etc. Try to use a range of approaches during a session as this will provide different ways for students to engage with the content.

Group work: you might consider using Discussion Boards, Padlets, Miro boards, group blogs etc. to enhance students’ ability to collaborate.

Managing information: you could encourage students to use OneNote, Evernote, RefMe, Diigo, Zotero, OneDrive, Teams, etc. to help them manage their work more effectively.

Assessment: you might suggest that students submit their work for assessment as a video, PowerPoint with voiceover, essay, blog etc. to provide a range of ways for them to evidence their learning.

You need to be careful here with any technologies suggested, especially any that might be used for assessed work. Assessing must be done using technology that has been incorporated into UCA’s suite of tools, software, etc. offered to staff and students for use. Only those technologies will have had due diligence processes conducted on them and been vetted for compliance with GDPR and OfS requirements for retention of data, etc.

- Feedback: you could try using blogs to provide formative feedback, or use the voice recording feature in, say, Blackboard’s Gradebook or Turnitin’s Feedback Studio to provide a short audio commentary on students’ work.

- Accessibility: in 2018 the Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) (No. 2) Accessibility Regulations came into force, which requires technology to be accessible. There is an emphasis on both the suppliers of the technology (to provide the tools) and the tutors using it to ensure content created in the technology is done in a way that makes it accessible to those with accessibility needs.

Importantly, you should ideally be confident with the technology that you intend to use. You don’t have to be a master, but you should be able to answer basic questions from your students. If you want to explore a particular technology, meet with your Learning Technologist before the session so that you can ask questions to help you build your confidence.

Very importantly, ask yourself whether all students will be able to access and use a specific technology. Determine whether the technology presents additional difficulties for students with specific learning difficulties. Check whether the technology can be accessed from both Macs and PCs, and if not whether it is available to students from the UCA Library.

It is also a good idea to have a back-up plan in case the technology doesn’t work in your session. For example, what will you do if students cannot connect to the Internet? You might consider printing off some key discussion questions relating to the topic so that the session can still continue if disaster strikes.

Lastly, it is advisable to try and get into your allocated teaching space at least 15 minutes early so that you can set up the technologies you are using. This might just be a projector, or it might involve you logging in to various applications. If you intend asking students to use computers, use this time to switch on all the computers as they can often take a while to start.

One more thing – if possible, make sure you have contact details for the correct support person/team to ask if you can’t get things to work. The UCA Technicians are usually able to respond within a few minutes, so keep their number handy so you can call if you need urgent assistance.

In-session

During the session, make sure that technology is not getting in the way of students’ learning. This can occur both through practical difficulties and through unnecessary distractions.

Action.

Circulate the room and check that all students can use the designated technology to accomplish the task. Resolve any problems quickly so that they can continue, or if the problem appears terminal (e.g. a computer won’t work or they can’t log in) ask the student to work with another student or group.

While you are circulating the room, make sure that students are not using technology for things not related to the task. Many students find it difficult to resist the urge to check social media, but this will distract them from learning. If you notice that students’ attention is starting to wander, use strategies to refocus their attention such as asking them to summarise what they have learned or setting them a new task.

You could also:

- Make sure you’ve prepared prompts to help students develop tasks.

- Break down tasks into bite-sized chunks so you can check in with students’ progress more easily. This will also support students to stay on track.

- When students are familiar with the technology, set times for the completion of tasks to help students keep focused.

- Give students regular encouragement. Some students will respond well to this attention and may continue working.

- If possible, provide a print out of instructions so that students can refer to it rather than taking time away from other teaching elements you need to be dealing with.

- Ask the student if everything is OK and if they need anything. Distraction may be due to a number of reasons including life outside of the session.

You might also consider ways of enabling students to use their personal technologies to contribute to the session. For example, you could ask them to work in small groups and use their phones or laptops to look up a range of perspectives on a given topic. This will need to be handled carefully. It can sometimes be difficult to get students off their phones again.

Post-session

Depending on the technology you are using, your students may be grappling with it after the taught session has ended. This is often the case with group activities involving blogs or other collaborative tools.

Action.

Make sure that your students know what you expect them to use the technology for during their self-directed learning time. Provide clear instructions and examples.

Make sure your students know what they can expect from you in terms of online engagement. For example, if you are asking them to use blogs give them an indication of how often you will be looking at their blogs, and whether you will be using them to provide feedback.

Make sure your students know who to contact if they have a technical difficulty. This may be you, your Learning Technologist, a member of the Technical team, or the IDS Team.

Tony Reeves, Former Subject Leader PgCert Creative Education

Updated Oct 2023 by Matthew Drury, Learning Technology Manager and Maxine Chester, Learning Development Tutor

DnA (Diversity and Ability) offer a full list of assistive technology (such as screen readers and notetakers) https://diversityandability.com/resources/

Online Learning Environments

An inclusive online learning space is particularly important for students whom you only meet online, e.g. at the Open College of the Arts (OCA).

The online meeting space is naturally inclusive to some extent in that students can meet from work or home. It is of particular value to those with caring commitments who may not be able to attend meetings at specified times. It can also be useful for students with mental health issues and those with physical difficulties who find accessing physical spaces problematic. Online meeting spaces are also crucial when working with students living abroad.

Good online spaces for tutorials include Skype, FaceTime, Zoom and Google Meet (the latter being available for all OCA students via their university email address). When students are abroad there can sometimes be issues around which platforms are allowed, for example the UAE government does not accept Zoom.

There will be students suffering from anxiety and those with minimal experience of technology, so make sure your instructions for using the online meeting space are clear.

Offer a choice or combination of methods to communicate the instructions. This could be, for example, dyslexia appropriate written information with supporting screen shots or images (see the British Dyslexia Association guidelines for further advice). And/or video animations or screencasts.

Allow time for getting the technical issues right during the first meeting and create advice on what to do when the tech fails or plays up. This could be moving to the phone in combination with the visuals onscreen if the audio fails, or turning the camera off but continuing with the audio when there are problems with broadband width and lagging. There will almost certainly be problems from time to time, so keep email communication open and suggest the student promptly emails if they are having problems.

Within the meeting instructions, briefly explain the shape of an online tutorial to help relieve anxiety and to make sessions clearer for holistic thinkers.

Create clear guidance on agreeing times and dates. And make sure you take into consideration international time zones.

The shape and content of the tutorial will be driven by the student and the work they have produced. To help the meeting run smoothly, you might ask students to submit a list of areas they wish to explore with you prior to the tutorial. This can be done in a shared google document where both the student and tutor can add to an agenda.

Ask students to document the meeting either by taking notes (which can be done by a support worker, member of the peer group or family member) or by making a recording. (At the OCA students studying at stage 1 receive a summary of the meeting from the tutor, then at stages 2 and 3 the student is asked to create a short reflective summary of the tutorial that the tutor can add to and comment on. This can be written, audio or video depending on the student’s preferences. This supports students to engage actively with the formative feedback and helps the tutor to gauge the student’s progress.)

Some students may feel uncomfortable with a face-to-face meeting, for example some autistic people. If this is the case, the bulk of a meeting can occur with the video cameras off and the focus on sharing images of the student work for discussion. A further alternative is to use the chat box provision built into Google Meet and Zoom. The chat box allows for files to be shared, for example images of the student work for discussion. Or student work can be visible via the video camera with the conversation taking place in the chat box.

Finally, consider where you are sitting for your sessions. What does the background say about you and the course? Is it welcoming? Could it be distracting for those with attention difficulties?

Rebecca Fairley, Programme Leader, BA (Hons) Textiles, The Open College of the Arts.

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Ruth-dancing-copy-1-1000X666.jpeg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Alice-Blog-1-1-397X137.jpg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/International-Womens-Day---Steps-into-HE-copy-1-1000X1270.jpeg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Laura-Quinn.jpg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Fig.1-Gatton,-M.-(2017)-The-People%C3%A2%C2%80%C2%99s-Library-%5BPhotograph%5D-At-httpsideas.ted.comwp-contentuploadssites3201706featured_art_protest_library.jpgresize=1024,585-(Accessed-06122023).%5B97%5D-copy.jpeg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Alice-Blackstock.jpg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Blog-Picture.jpeg)

/prod01/channel_13/creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Sophie-Image-copy.jpg)