Introduction

Inclusivity incorporates the legal requirements of the Equality Act 2010, together with accepted good practice. Inclusivity covers both what people learn and how they learn. Every aspect of teaching and learning should have inclusivity at its core. The nine protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010 are:

|

age; disability; gender reassignment; marriage and civil partnership; pregnancy and maternity; |

race; religion and belief; sex; sexual orientation. |

Government funding for disabled students has undergone review, and significant cuts have been made to some of the funds universities were receiving. Learning support assistance is no longer funded, which is impacting on, for example, studio assistance, note-taking, help in keeping students on task and assisting in understanding. The government believes the cost of one-to-one support can be reduced – or even eliminated – if universities create a more inclusive environment for their students.

At the same time, the student population has been changing as society has become more diverse and as a result of the UK’s success in attracting international students. Their needs must be met under the Equality Act and UCA’s commitment to inclusive practice.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Intersectional Thinking

"Diversity initiatives must always embrace intersectional thinking and should not be wary of addressing the needs of a whole population of students". (Haddon, 2019:8)

There is now some disagreement about the exact meaning of the term. Hill Collins and Bilge (2016:25) say intersectionality ‘references the critical insight that race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, ability, and age operate not as unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but rather as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities.’

It is perhaps most usefully seen as a reminder that we are all clusters of experiences. Being dyslexic, say, or an international student cannot be seen in separate bubbles: dyslexic students may, for example, have mental health issues and/or be wheelchair users; the international student may be deaf. And the way these differences intersect in individuals is important to how we might support them.

The importance a student attaches to their disabilities or differences may also fluctuate: there may, for example, be periods when identifying as dyslexic or LGBTQ+ is more important to a student than, say, their ethnicity or international status. Their social background may also influence their attitude towards difference and disability.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Building an Inclusive Practice

Among the benefits for you when your teaching is fully inclusive are:

Students are more likely to be successful in your classes if you are creating activities that are relevant to their different backgrounds, cultures, abilities and learning styles.

They are more likely to engage with the ideas that you are offering – students connect with ideas and materials that are relevant to them – and to be comfortable developing ideas and asking questions in class.

You are therefore likely to spend less time doing one-to-one work or in email correspondence with struggling students.

|

Equality, diversity and inclusivity in the curriculum |

I do this |

I need to consider this |

|

1. Regularly review curriculum issues including race, gender, religion or belief, sexual orientation, disability and age |

|

|

|

2. Periodically assess the relevance to contemporary society of course materials |

|

|

|

3. Periodically assess the appropriateness of the modes and methods of delivery of the curriculum, in its widest sense |

|

|

|

4. Consider, in terms of coursework, resources and so on, how people and places are represented and whether or not they are stereotyped |

|

|

|

5. Value the diversity included in the student body |

|

|

|

6. Assess and revise your teaching methods periodically |

|

|

|

7. Consider what are the most appropriate methods, timing and formats of assessment for the students you teach |

|

|

|

8. Assess whether the materials you provide for your students in both print and web format meet the current accessibility standards for disabled students |

|

|

|

9. Consider what to do if any colleagues or students use inappropriate language with respect to those who are disabled or hold religious beliefs or use language which is sexist, homophobic or ageist |

|

|

Minoritised ethnicities

Although proportionately greater numbers of minoritised ethnicity students enter Higher Education (HE), there are significant gaps in attainment between ethnic groups across the sector.

In Art and Design HE there is a 33% gap between the proportion of Black British African and Black British Caribbean students qualifying with a 1st or 2:1 when compared with their White counterparts (Finnegan and Richards, 2016).

“The diminishment of “social justice” in many university strategic plans by the enlargement of ‘internationalisation’ agendas is testimony to the dissonance that exists between the principles of open access and the realities of institutional privilege.” (Shilliam, 2014)

There are a number of ways in which we can address these inequalities.

In the curriculum:

Create more diverse reading lists and key visual references;

See a diverse curriculum as integral to all students learning, not as an optional add-on for BAME students.

Engage Student Union BAME liberation groups to explore opportunities for co-creating curricula.

In the studio

Ensure that all students have equal access to tutors without having to identify as needing help.

In assessment and feedback

Frequent meaningful formative assessment benefits all students BUT it benefits lower achieving students more than higher achieving students. This makes it a valuable tool for addressing differences in attainment.

In staffing

Where the course team is not reflective of the ethnic diversity of the student body, efforts can be made to attract a more ethnically diverse staff, for example by advertising positions on forums aimed at addressing ethnic diversity in the creative industries.

Guest speakers and industry professionals from ‘non-white’ backgrounds can be selected as short-term measures to address a lack of ethnic diversity.

Supporting LGBTQIA+

|

Unhappy LGBTQIA+ students |

96% |

|

Gay youths distressed by bullying |

85% (NUS) |

|

Trans youth: |

|

|

Attempted suicide |

48% |

|

Seriously considered suicide |

56% |

|

Experienced harassment at college |

81% (SU UCA) |

Gender reassignment is a long (and expensive) process; trans students may be taking hormones/having psychological support throughout their university years. They will miss classes, lectures and may feel isolated because of this. Changing their names by deed poll does not give them privacy since they must use their birth names on entrance forms and thus need to explain themselves.

How to help:

- Language: check that this includes marginalised communities, e.g. ‘Good morning, everyone’ will cover every identity. (NB There are 50 different genders. See online Genderbread material).

- Don’t assume anyone’s identity.

- Trust community definitions of what is homophobia/transphobia.

- Be aware that everyone in the room might not know or understand issues surrounding LGBTQIA+: not all communities are liberated; there is more than one queer experience.

- Understand your privilege.

- Challenge homophobia, biphobia and transphobia.

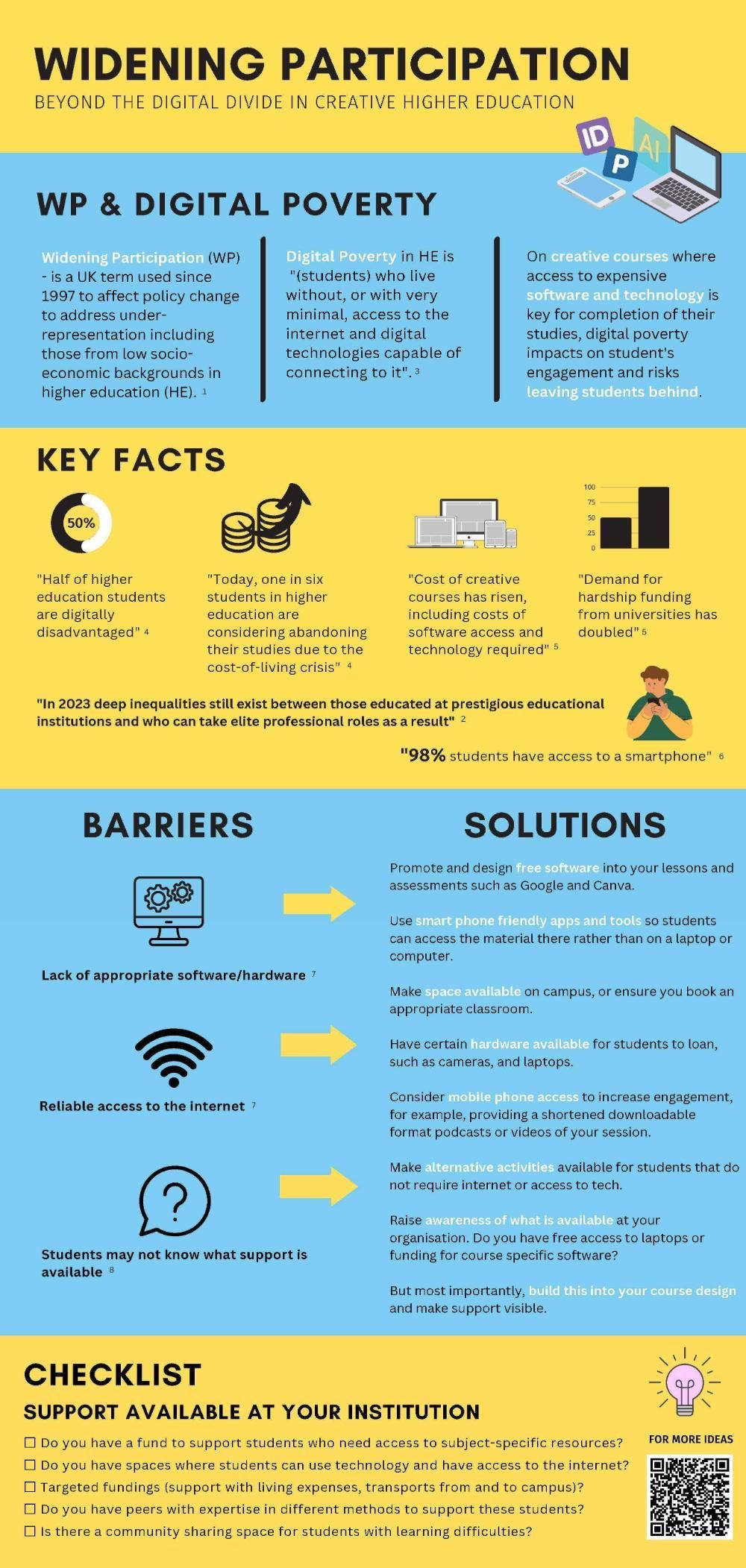

Widening participation

There is a tendency to conflate access and participation, and emphasis is placed on access. Less attention is paid to the very varied needs of those who gain access through widening access schemes, and retention figures are lower than for other groups. It is often seen in terms of young students from disadvantaged backgrounds. But widening participation (WP) is much wider than that, and, e.g. mature students, those who may also be carers, forced migrants and travellers should all be included and their diversity supported.

Finally, despite a great many Outreach and other programmes to bring in and support WP students, there is very little robust evidence of the value of this effort. And as John Blake of the Office for Students says: ‘We can’t share what works, and we can’t make it work better, if we don’t actually know what does work (OfS, 2022).’

What can we do?

‘I have heard more often than I would like that students feel their providers fell over themselves to bring them into higher education, but interest in their needs trailed off the moment they were through the door (OfS, 2022).

- We need to think very clearly about the HE environment we are creating for WP students and on what basis, including:

- Specific targeted approaches particularly for care leavers and disabled learners (Moore et al., 2013).

- Fostering a sense of belonging and learner identity, both of which are key to student retention. WP identity may be destabilised by radical shifts, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Campbell, 2020).

- Encouraging supportive peer relationships and developing ‘meaningful interaction’ between tutors and students (Moore et al., 2013).

- Changing the language of HEIs, particularly around assessment, which also has an impact on retention (ibid).

- ‘Offering an HE experience that is relevant to students’ interests and future goals’ (ibid).

And, says, Blake (2022), ‘Evaluate, evaluate, evaluate.’

Engaging with International Students

As an institution, to what extent...

Are clear roles and responsibilities provided across all services and functions to clarify their contribution towards internationalising HE?

Are international and intercultural experiences, partnerships and collaborations encouraged within relevant institutional policy and curriculum structures?

Are cultural diversity and international experiences or knowledge regarded and used as a learning resource within the academic community?

Are a diverse range of developmental opportunities provided and promoted, throughout and beyond HE, to enable the whole academic community to contribute to, and benefit from, the internationalising of HE?

Are discrimination and barriers (internal or external) to participation and success eliminated within all policies, processes, systems and the design of curriculum?

Are reward and recognition systems used to value and motivate individuals’ contribution to internationalising HE?

Are operational systems and procedures sufficiently resourced to facilitate internationalising HE?

Is a visionary approach to internationalising HE and inspiring leaders promoted across the organisation to take action?

As individuals, to what extent…

Are you creating and seeking on-going personal and professional learning opportunities to develop global and cultural understanding through, for example, work or study abroad, language acquisition, international networks, conferences, courses, festivals, cultural events or travel?

Are you critically reflecting upon and responding to personal prejudices, biases and assumptions as part of your practice?

Are you drawing on individuals/diverse learning histories, narratives and experiences?

Are you using flexible and inclusive approaches that appreciate and respect individual differences in knowledge, education and culture?

Are you enhancing an understanding of the academic benefits and value of contributing to, or participating in, activities associated with the process of internationalising HE?

Are you contributing to international scholarly activity and knowledge exchange?

Are you seeking opportunities to understand the social, discipline, and cultural contexts that underpin what is learned and how?

Are you leading and supporting others to reflect on and engage in continual learning and development in relation to internationalising HE?

From: Tomasz John Workshop, How to engage with internationalisation (UCA Epsom 5.1.17)

Transitions into FE and HE

An analysis of Hughes, G. and Smail, O. (2015) ‘Which aspects of university life are most and least helpful in the transition to HE? A qualitative snapshot of student perceptions’ in: Journal of Further and Higher Education 39: 4, pp.466-480.

The findings of this study suggest that transition support may gain better student engagement if it is initially focused on social integration and student wellbeing and lifestyle. Universities may also wish to pay more attention to the impact of administrative processes failing to meet student needs in the transition period. It is not unusual for students going through transition to experience psychological distress, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, a reduction in self-esteem and isolation.

This study asked students to respond to short open statements to establish the dominant positive and negative preoccupations in the process of transition – on the understanding that ‘if interventions begin where students are most preoccupied, they may be more likely to engage students at a key moment and open the possibility of addressing other problems while their attention is fixed.’

Social Support – Dominant theme both positive and negative

- Having friends in the same situation that I can work through with and share my worries.

- Being left out.

- Clear indications that whether or not a student had made friends was a key preoccupation at this stage of the first year.

- I have found the activities to get to know the lecturers and other students useful as they made me get to know people.

- Being put into very large lectures during induction week and not having any sort of team building exercises to get to know anyone [was unhelpful].

- Interaction with staff, in particular lecturing staff, was also significant.

- Psychological mind-set and lifestyle

- Identifying their own thinking and behaviour as important to successful transition. Positive and negative.

- The welcome talk was very motivational and useful. Having someone congratulate us on getting into university and saying we can all do well and to believe in ourselves was great.

- I feel like we were bombarded with paper and information in my first few weeks … made me feel so overwhelmed and scared.

University actions

- Real and measurable impact on transition, retention and performance.

- Students generally expressed a preference for induction sessions in small groups to allow for team building and socialisation. Large gatherings in lecture theatres attracted more negative comments.

- Information overload.

Support

- Importance of knowing and understanding the support that was available (professors, academics, institution).

Organisation

- Small administrative and organisational oversights and problems can apparently have a weighty negative impact.

Academic concerns

- Academic concerns not a major pre-occupation at this stage – focus on social, personal and organisational aspects of university life.

Conclusions

Whilst student transition remains a complex and multi-faceted process, this study suggests that universities may benefit from focusing their initial interactions with students on supporting social integration, promoting positive thinking patterns and behaviours and challenging negative thinking and lifestyle choices. Institutions may also wish to consider the potential impact of all early activities on student transition, whilst remaining confident that it is possible to positively influence this process.

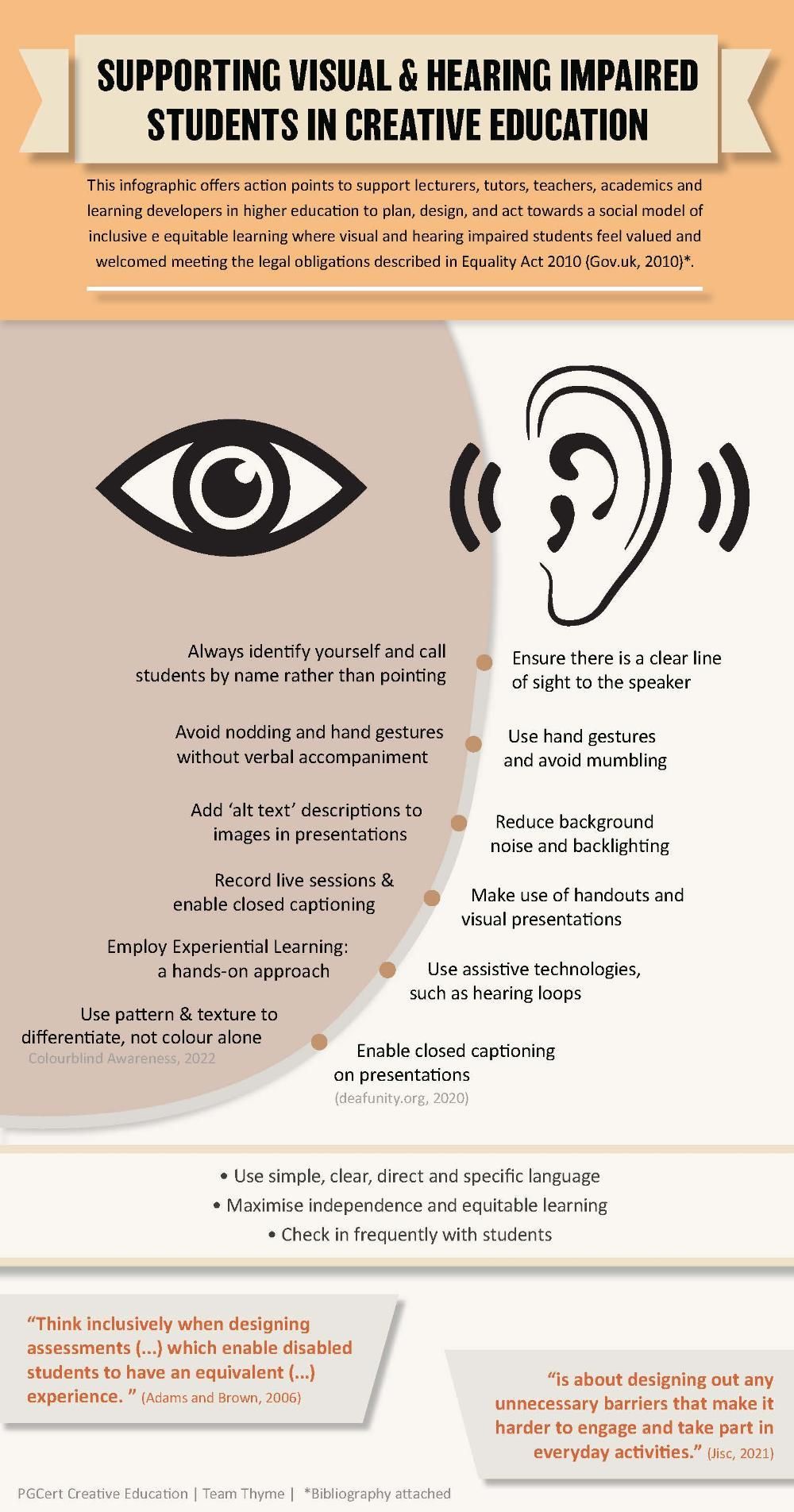

Disability

Rather than use the medical model of disability, which looks at what is ‘wrong’ with the person, UCA are committed the social model of disability which supports that people are disabled by barriers in society, not by their impairment or difference. “Barriers can be physical, like buildings not having accessible toilets. Or they can be caused by people's attitudes to difference, like assuming disabled people can't do certain things. The social model helps us recognise barriers that make life harder for disabled people. Removing these barriers creates equality and offers disabled people more independence, choice and control” (Scope, 2022)

Recognising the importance of equal opportunities and inclusivity, UCA have implemented policies and practices to accommodate the needs of students with disabilities. These accommodations aim to ensure that students with disabilities have equal access to educational opportunities, facilities, and services. You can find more on ‘support for success’ here.

"Deafness is not pathological, but merely another way of being normal, or possibly even a way of being better than normal, [some] claim. Despite such assertions, however, much of the hearing world remains unconvinced, and continues to think of deafness in negative terms." (Cooper, 2007)

The categories deaf and hard of hearing cover a wide range of hearing losses, from a profound to mild loss. Most deaf or hard-of-hearing students will access some sound through hearing aids or cochlear implants and will communicate through spoken language but some will have no access to sound at all. For these students their first language will be sign language (BSL).

Many deaf or hard of hearing students will use lip reading too, but expect students to be able to understand roughly 30% of a communication when lip reading (p, b and m are particularly difficult to recognise).

To catch a deaf student’s attention, you may need to touch them lightly on the arm or shoulder. Aim to be facing the light when you talk and do not stand with your back to the window as that throws your face into shadow and makes lip reading difficult. Talk slightly slower than normal but without any exaggerated lip movements as this makes lip reading more difficult. You may need to repeat yourself several times.

If your student is using an interpreter, remember to look at the student: you are not talking to the interpreter.

Provide handouts, Powerpoints etc. in advance; and provide all feedback in written form.

"As a deaf student, I’m used to being excluded. Universities must do better."

If there are hearing loops in lecture rooms, check they are working. (They need to be checked once a week and thoroughly checked once a year.) Make sure you do not move away from the microphone while talking.

Some deaf students may have Roger pens or radio aids and will ask you to wear them. These devices send your voice directly to the hearing aid or cochlear implant and make it easier to follow in a classroom environment. (In group discussions, the Roger pen will sit in the centre of the group to pick up all the voices.)

If you are using videos/television in a lecture, where possible have subtitles; and if subtitles are not available provide a transcript of the video. Avoid talking while students are reading the subtitles since they cannot lip read and read the subtitles at the same time.

Avoid timetable changes so that loops/other equipment can be in place and interpreters/lip readers can plan their own timetables.

The work interpreters do is tiring. If there is only one interpreter in a long lecture, make sure there is a 10-minute break in the middle. (It is preferable to have two interpreters working together swapping places after 20 to 30 minutes; the translation is likely to become less accurate over time.) Do not thank the interpreters: they work for the deaf student, and deaf students will do this themselves.

"There is no universal deaf experience. But we’ve all experienced exclusion to some extent."

It is useful for students to have a glossary/vocabulary list in advance since it is very difficult to lip read unknown words. (This list will support understanding for many other students too.)

Give an overview of a lecture in advance to help with lip reading, and make it clear when the topic is changing so that deaf students understand there is new language to come. (This holistic approach supports students with SpLDs and many other students too.)

In sessions where you may have discussions as well as talks, make sure that deaf students know when to join in, and make sure they are included in jokes and funny stories by repeating them back.

Top tips

- Get the student’s attention before speaking to them – either by saying their name or tapping them on the shoulder.

- Make sure they can see your face so that they can watch your mouth and see your expression. This will help them to interpret what you are saying to them.

- Hearing aids and cochlear implants work best at a distance of 1 to 2 metres. Students using these devices will hear you best if you are close to them and in front of them.

- Repeat words, requests and questions.

- Repeat comments and questions from other students in the class.

- Hearing aids and cochlear implants amplify all sound – if the room is noisy, a deaf or hard-of-hearing student will hear less and you may need to repeat yourself.

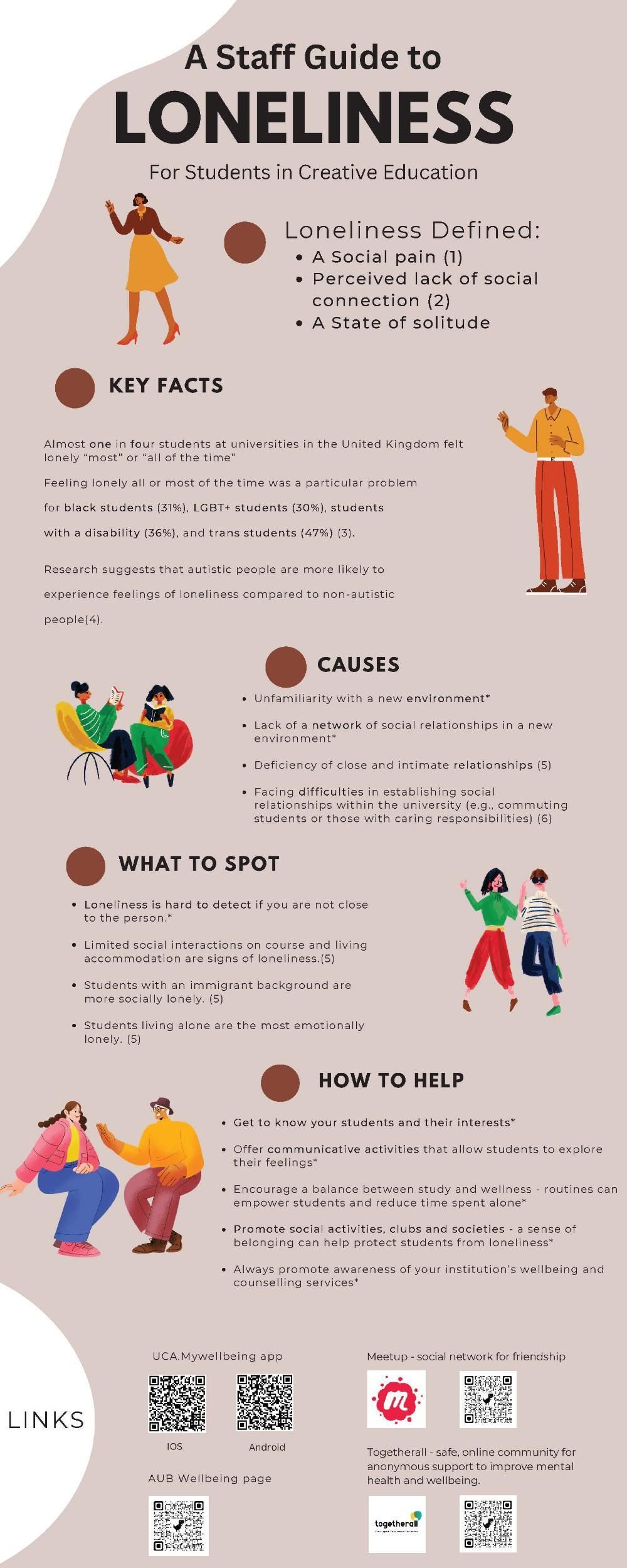

Mental Health and Wellbeing

The term positive mental health is often used interchangeably with the term mental wellbeing. Current research on wellbeing has two distinct perspectives:

The hedonic approach, which focuses on happiness and defines wellbeing in terms of pleasure attainment and avoidance of pain;

The eudaimonic approach, which focuses on meaning and self-realisation and defines wellbeing in terms of the degree to which a person is fully functioning.These two views have given rise to different research interests and a body of knowledge that is in some areas divergent and in others complementary.

- 81% of students affected by mental health difficulties

- 91% of LGBTQ+ students experienced mental health challenges

- 27% of students said they don't have any friends at university and identified loneliness as a significant issue

- 46% felt their university supported those with mental health challenges,

- 63% said they prioritised mental health provision when choosing a university. (Student Mental Health Study 2022)

- 450% rise in mental health declarations in HE 2010-20 (UCAS June 2021)

- 49% of students with an existing condition do not share any details about their mental health concerns because they do not understand what selecting that option actually means. (OfS, 2023)

Warning signs of student distress

- Changes in mood e.g. elevated or decreased mood, increased anxiety

- Irritability or tearfulness

- Restlessness

- Reduced appetite and weight loss

- Reduced concentration and memory

- Loss of initiative or desire to participate

- Decrease or increase in speech speed

- Increased difficulty making decisions

- Placement non-attendance e.g. unexplained absence or sick leave

- Reduced communication or withdrawal

- Changes in presentation and cleanliness

- Reduced performance

- Poor organisation and time management

- Changes in ability to think logically

Issues of non-disclosure

- Fear they will not get in; stigma/fear of being judged

- (UMHAN, 2017)

- Cultural differences: Reliance on prayer or faith healers; belief that it is a Jinn possession or Evil Eye

- (Ahmed, 2012)

- Source of shame; distrust of the medical profession.

Additional risks for international students

- High expectations

- Lack of familiarity

- Restrictive conditions

- Home ways of learning don’t fit

- Course selection mismatch

- Pride hides vulnerability; stops help seeking

- Working psychological over-time to fit in.

(UKCISA)

‘The move to a new environment is one of the most traumatic events in a person’s life and in most sojourners some degree of culture shock is inevitable’

Symptoms associated with culture shock

|

Low self-esteem |

Bitterness |

Depression |

Helplessness |

|

Low morale Social isolation Dissatisfaction with life |

Homesickness Disorientation Anxiety |

Role strain Identity conflict Self-doubt |

Personality disintegration Irritability Fear |

A key trigger

Real or supposed attacks on national identity

(Brown and Brown, 2013:397)

Co-occurrence

Over 50% of people with a mental disorder are likely to develop another mental or physical condition in the first 1-2 years after developing the first (Thompson, 2023)

Definitions

Note that researchers may mean slightly different things when referring to poor mental health, e.g. Lewis and Bolton (2023) work with two definitions. Their data analysis ‘is based on a narrow definition of poor mental health, namely a health condition or disability reported by the student to their university or college that has a substantial impact on that student’s ability to carry out day-to-day activities and has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months’. When they are ‘describing the mental health related work of the OfS, universities and colleges, and other organisations, they use a definition that covers a broader range of experiences, including clinically diagnosable mental health conditions and mental distress that has not been linked to a diagnosis.’

Stepchange: Mentally Healthy Universities (2020)

Co-developed with Student Minds. ‘A strategic framework for a whole university approach to mental health and wellbeing at universities. It calls on universities to see mental health as foundational to all aspects of university life, for all students and all staff.’ (Lewis and Bolton, 2023: 36-37)

The University Mental Health Charter (2019)

‘A set of principles universities can commit to working towards to improve the mental health and wellbeing of their communities. The charter was developed by Student Minds with the UPP Foundation, the OfS and NUS.

‘The framework provides a set of evidence informed principles to support universities to adopt a whole-university approach to mental health and wellbeing.’ (Lewis and Bolton, 2023: 37-38)

Resources

AdvanceHE Education for Mental Health Toolkit https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/education-mental-health-toolkit

Mindbox 24-hour instant access online therapy centre to help students with, among other things, stress, anxiety, performance nerves, panic attacks. Various subscription options.

Headspace Different guided meditation sessions to help with areas that you need to work on.

Calm Similar to Headspace. Free trial.

Student-led initiatives

Nightline: Trained student volunteers answer calls, emails and messages in person to fellow students;

Student Minds: Researches and campaigns on mental health issues. It trains volunteers and supports student-led societies

Students Against Depression: Website offering advice, information, guidance and resources for students with depression and suicidal thoughts.

The Samaritans Step by Step: Service expanded into the higher education sector

UCA initiatives

Togetherall. A digital mental health and wellbeing platform offering safe, anonymous online peer support 24/7. Togetherall.com

The myWellbeing app helps students build healthy habits and supports positive wellbeing. Download from the iOS App Store or Google Play.

An eating disorder is a mental health condition where food is controlled to cope with difficult feelings and other situations. The best current estimate of people with eating disorders is 1.25 million.

With treatment, most people can recover from an eating disorder but it may take some time and will be different for everyone.

The most common eating disorders are:

- Anorexia nervosa (controlling weight by not eating enough, doing too much exercise or the two together);

- Bulimia (losing control over how much you eat and then taking drastic action to avoid putting on weight);

- Binge Eating Disorder (BED) (eating large portions of food until you feel uncomfortably full);

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) (symptoms do not exactly fit expected symptoms for any specific eating disorders; the most common eating disorder);

- Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) (avoiding certain foods, limiting how much is eaten or both; unconnected with beliefs about weight or body shape; could include: negative feelings about smell, texture or taste of certain foods; response to an upsetting past experience with food, e.g. choking; not hungry or not interested in eating).

Research is beginning to show there is a significant overlap between neurodivergence and those struggling with eating disorders.

Nearly 20 percent of individuals diagnosed with ARFID also have autism.

A third of individuals with ARFID reported avoiding foods due to sensory issues, a trait present in many neurodivergent individuals.

Individuals with anorexia nervosa report higher rates of autistic traits.

Female-identifying individuals with ADHD are nearly four times more likely to develop an eating disorder.

Warning signs incude:

- Dramatic weight loss;

- Lying about how much they’ve eaten, when they’ve eaten or their weight;

- Eating a lot of food very fast;

- Going to the bathroom a lot after eating;

- Exercising a lot;

- Avoiding eating with others;

- Cutting food into small pieces or eating very slowly;

- Wearing loose or baggy clothes to hide weight loss.

What to do:

This needs care. Someone with an eating disorder may not realise they have one. They may also deny it or be secretive and defensive about their eating or weight. Take advice from your wellbeing centre.

Adapted from: NHS ‘Overview - Eating Disorders’ at: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/behaviours/eating-disorders/overview/

The eating disorder charity Beat also has information on: ‘What to do if you’re worried about a friend or family member’; and ‘What to do if you’re worried about a colleague.’

The World Health Organisation identifies bipolar as one of the top causes of lost years of life and health in 15 to 44 year olds.

Bipolar is characterised by significant mood swings including manic highs and depressive lows that may last several weeks or even months. Most people with bipolar swing between mania and depression.

During manic phases, sufferers may feel very happy, have lots of energy and feel very creative. They may not want to eat or sleep, and spend money recklessly. They may talk quickly and be easily irritated.

When feeling low, sufferers may not feel able to engage with the world. This is not self-indulgence or laziness; it is not a choice.

- One in 50 people in the UK has bipolar.

- It takes an average of nine years to get a correct diagnosis.

- Many sufferers still lack support and treatment to help them live with it.

- 67% were given no self-management advice when they were first diagnosed.

- It increases the risk of suicide in sufferers by up to 20 times.

Many bipolar sufferers still feel a stigma attached to their illness along with guilt and self-blame:

‘[Bipolar students] found it difficult to ask for their assignment deadlines to be extended … “I felt this big sense of shame of not being good enough to get things done on time without needing the extra support and help.”’

‘If you're living with this illness and functioning at all, it's something to be proud of, not ashamed of. They should issue medals along with the steady stream of medication.’ (Carrie Fisher, Wishful Drinking, 2008)

From: Molly Shindler Stigma: blame and guilt 8 Oct 2019

Neurodivergence

Neurodiversity is the idea that neurological differences like dyslexia and ADHD are the result of normal, natural variation in the human brains and mind.

Dyslexia is a specific learning difficulty that mainly affects the development of literacy and language related skills. It is likely to be present at birth and to be life-long in its effects. It is characterised by difficulties with:

- phonological processing (sounds);

- rapid naming;

- working memory;

- speed of processing information;

- the automatic development of skills that may not match up to an individual’s other cognitive abilities.

Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of:

- language;

- motor co-ordination;

- mental calculation;

- concentration;

- personal organisation.

But these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia. It tends to be resistant to conventional teaching methods, but its effect can be mitigated by appropriately specific intervention, including the application of information technology and supportive counselling.

A good indication of the severity and persistence of dyslexic difficulties can be gained by examining how the individual responds or has responded to well-founded intervention.

In addition to these characteristics, the British Dyslexia Association (BDA) acknowledges the visual and auditory processing difficulties that some individuals with dyslexia can experience, and points out that dyslexic readers can show a combination of abilities and difficulties that affect the learning process. Some also have strengths in other areas, such as design, problem solving, creative and/or interpersonal skills.

Dyslexia can occur despite normal intellectual ability and teaching. It is constitutional in origin, part of one’s make-up and independent of socio-economic or language background.

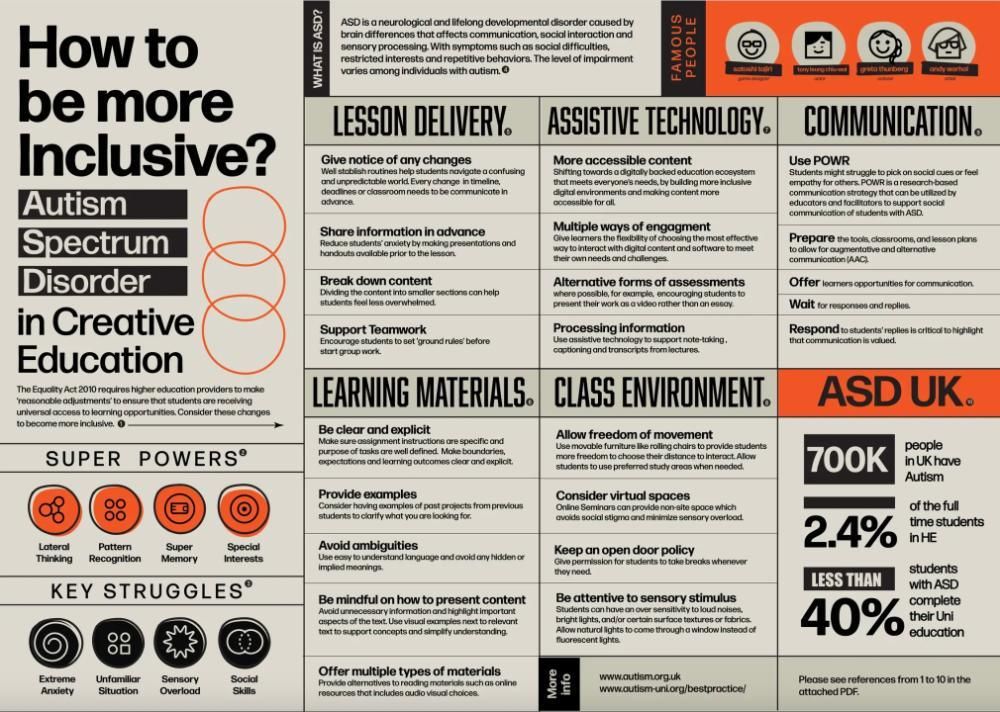

‘Specialist training on supporting students on the autism spectrum should be mandatory for all teaching and support staff’ (Haswell et al., 2013).

Autism is a developmental disability/condition that affects more than one in 100 people. No two autistic people will be quite the same, nor will they necessarily conform to widely-held views of autism, e.g, not all autistic people avoid eye contact. The three main difficulties for autistic students are: social communication, social interaction, social imagination.

There is often an overlap between autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, ADHD and epilepsy. Up to 80% of autistic people face mental health challenges, most common among these being anxiety and depression; roughly one-third may also have OCD; some have eating disorders; there is also some suggestion that autistic people may suffer from gender dysphoria.

Social communication

May have difficulty understanding or generating conversation; may be confused by jokes, metaphor and sarcasm.

Be clear and concise; give time to process information; give clear feedback; avoid metaphor or irony.

Social interaction

May have difficulty with friendships and understanding what is appropriate behaviour.

Social imagination

May be imaginative in conventional sense, but difficulties may include: imagining outcomes or predicting what will happen next in social situations; understanding or interpreting people’s thoughts or feelings.

Autistic people may also have a love of routines, special interests, sensory difficulties.

Love of routines

To make the world less confusing, autistic people may set up rules or rituals which they insist on following. They often prefer their day to be ordered to a set pattern. Unexpected changes to the timetable may create anxiety and distress.

Give students advance notice of any change to timetable or deadlines; every change needs marking clearly on the intranet too.

Special interests

Autistic people may develop an intense, sometimes obsessive interest in a hobby or collecting.

Sensory difficulties

All senses may be affected. Autistic people may be over or under sensitive to sensory stimulation, e.g. bright lights, strong smells, loud noises, touch may cause anxiety or pain.

There may also be reduced body awareness; autistic people may bump into objects, have difficulty with motor tasks, rock or spin to regain balance or deal with stress.

‘Stimming’ – repetitive actions or words – may help to soothe autistic students when coping with pressure and anxiety. This may include flapping arms, spinning or rocking. It is normal, and it is important that lecturers recognise and accept it in their classrooms.

The characteristics of autism have been largely established through the study of autistic boys. Some autistic students (usually girls) may appear to have been misdiagnosed, they seem so ‘normal’. The likelihood is that they work extremely hard to fit into the neurotypical world – and go home each evening exhausted by the effort. From an early age, they may have been watching and imitating other children/people so that they look ‘right’, while fearing that they will do something ‘wrong’. Watch out for stress and depression in these students. They may also have been missed or misdiagnosed, so work as if there is at least one autistic student in each of your classes. (This will help everyone.)

Roughly 2.4% of the UK student population has been diagnosed with autism; less than 40% of these students finish their degrees. ‘Many studies have emphasized that autism stigma and a lack of autism knowledge, especially among academic and pastoral staff, has a negative impact on autistic students’ mental health as it makes them less likely to seek support, and less likely to get appropriate support when they do reach out’ (Scott et al. 2022).

Even those who see themselves as knowledgeable about autism may offer poor support: there is ‘an attitude-behaviour gap’ (von Below et al., 2021).

Autistic perspectives can lead to unique ways of seeing the world along with idiosyncratic talents and abilities; enthusiasm, punctuality, determination and reliability are among the many qualities that students on the autism spectrum may bring to university (NAS, no date). Other strengths include ‘an ability to maintain intense focus, to adopt unconventional angles in problem solving, or to spot errors that others may overlook’ (ibid). The contribution that autistic people can make is being recognised by many businesses across the world (Fabri et al., n.d.).

Assignments: Autistic students may have difficulty in interpreting ambiguity. Make instructions clear (unless there are areas of an assignment that are purposely ambiguous) as well as learning outcomes. Also make it clear roughly how long each aspect of an assignment should take. Autistic students may not be able to distinguish between important elements and more minor ones.

Resource/reading lists: Make it very clear what is Essential and what is Optional. Some autistic students may read everything and then have no time to complete their assignments. Think also about what other advice/guidance might be given around your resource lists. This may benefit everyone.

Teamwork: With their social difficulties, autistic students may have particular difficulties with teamwork, and they have a right to an alternative under the Equality Act 2010. Teaching teamworking theory would be valuable. You could assign roles to students and make it clear what those roles entail. It may also be useful to assign marks for the way teams work together.

‘People have to bear in mind that if you have AS you have probably been bullied for most of your life’ (Beardon & Edmunds, 2007:243).

Note: the term ‘Aspergers’ has been ‘retired’, but you may meet autistic students who still use it because it has become part of their identity. ‘Autism Spectrum Condition’ is preferred to the term ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder’. Research also suggests that most autistic people prefer the term ‘autistic people’ to ‘people with autism’.

A chemical problem that undermines the brain’s management system. Around 50% of those with ADHD may also have dyspraxia; another 50% dyslexia; some will have both. Around 20 to 50% are likely to be autistic.

Three ‘presentations’: hyperactive/impulsive; predominantly inattentive; a combination of the two (the majority group). Symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity tend to decline in adulthood.

Misdiagnosis: many may have been assessed as bipolar or having borderline personality disorder or other disorders; over 80% (est.) have not been diagnosed.

Driven by strong emotions, which may be at the heart of their difficulties, with mood swings across the day. For those with ADHD and autism, there will be an ongoing internal battle between the desire for adventure vs. routine; freedom vs. structure; spontaneity vs. predictability.

Characteristics at university:

Inattention/distractibility (though can over-focus)

- May involve losing track of time, forgetting appointments or failing to eat; losing track in the middle of a conversation.

Difficulties with:

- shifting attention, dealing with background noise, listening to lectures, starting assignments;

- routine tasks such as scheduling; reading without skipping lines; missing words out in essays and misspelling.

Organisation and memory problems

- Difficulties with:

- planning, time management and prioritizing, learning from experience, planning ahead;

- forgetting and losing things;

- arriving late and rushed or missing appointments.

Hyperactivity

- May be unable to sit still in lectures and have to leave; fidgeting.

Impulsiveness

- May blurt out things in lectures or seminars;

- Need for immediate gratification can lead to addiction problems;

- May seek out high-risk situations, chop and change or start in the middle of things.

Procrastination

- Probably intractable.

Sleeping difficulties

- Probably intractable without medication.

Mental health

- Almost certainly have depression and/or anxiety or other disorders.

Possible strengths

- Creativity, originality, big picture problem-solving skills; high energy can be very productive; risk-taking tendency may lead to discoveries, hyper-focusing may lead to seeing things others do not; can be very determined and never give up; resilient and generous; entrepreneurial skills.

Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD), also known as Dyspraxia in the UK, is a common disorder affecting fine or gross motor co-ordination in children and adults. This lifelong condition is formally recognised by international organisations including the World Health Organisation. DCD is distinct from other motor disorders such as cerebral palsy and stroke and occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. Individuals may vary in how their difficulties present; these may change over time depending on environmental demands and life experience.

An individual’s coordination difficulties may affect participation and functioning of everyday life skills in education, work and employment. Children may present with difficulties with self-care, writing, typing, riding a bike and play as well as other educational and recreational activities. In adulthood many of these difficulties will continue, as well as learning new skills at home, in education and work, such as driving a car and DIY. There may be a range of co-occurring difficulties which can also have serious negative impacts on daily life. These include social and emotional difficulties as well as problems with time management, planning and personal organisation, and these may also affect an adult’s education or employment experience.

Adults in college and university commonly have the following difficulties in their studies:

- literacy;

- planning and organisational ability;

- working memory;

- speed of working;

- spoken language;

- visual perceptual and spatial skills.

Gross motor coordination skills

- Poor balance and rhythm, e.g. bicycle riding or dancing.

- Poor posture and muscle tone; clumsy gait and movement.

- Poor hand-eye coordination, causing difficulties with bat and ball sports and car driving.

Fine motor skills

- Lack of manual dexterity, and poor manipulative skills, causing problems in many areas such as:

- grooming and dressing;

- housework and cooking;

- DIY and craftwork;

- handwriting and keyboarding.

Speech, language and oral skills

- Continuous and/or repetitive talking.

- Difficulty organising content and sequence of language.

- Problems with pitch, volume, rate and pronunciation.

- Difficulty listening to people; can be tactless and interrupt frequently.

- Tendency to take things literally; may listen but not understand.

- Difficulty reading non-verbal signals, including tone and pitch of voice.

Perception (i.e. interpretation by the different senses)

- Poor visual perception.

- Lack of awareness of body position in space, causing tripping, bumping and spilling.

- Poor sense of time, speed, distance or weight.

- Poor sense of direction and left/right discrimination.

- Poor eye-movement e.g. keeping place while reading or looking from TV to magazine.

- Learning, thought and memory.

- Unfocused and erratic; may become messy and cluttered.

- Poor short-term memory; may lose or forget things.

- Poor sequencing, causing problems with maths, spelling and copying sounds.

- Difficulty following instructions, especially more than one at a time.

Emotion and behaviour (These are not direct symptoms of dyspraxia, but a reaction to it)

- Impulsive and easily frustrated; difficulty working in teams;

- Slow to adapt to new or unpredictable situations, often avoiding them;

- Tendency to be stressed, depressed and/or anxious; may have difficulty sleeping;

- Prone to low self-esteem, emotional outbursts, phobias, compulsions and addictive behaviour.

Many of these characteristics are not unique to people with dyspraxia, and not even the most severe case will have all the above characteristics. But adults with dyspraxia will tend to have more than their fair share of coordination and perceptual difficulties.

35-40% are also dyslexic; 50% also ADHD; only 10% are likely to have no overlap with other specific learning differences (SpLDs).

Tourette Syndrome (TS) indicators include muscular tics, vocal or phonic tics, disinhibited thoughts, emotional differences including difficulties in emotional regulation, obsessive compulsions and rituals. Tics, thoughts and compulsions have a habit of occurring when they are least wanted, and purposely trying to repress them can make the urge become stronger and stronger until a release becomes inevitable.

Tics can be divided into two types:

- Muscular tics - Rapid and repetitive movements of one muscle group, such as eye blinking, shoulder shrugging, squinting, or facial grimacing, hyperventilating, head nodding, stomach contracting.

- Vocal tics - Repetitive sounds that can include throat clearing, sniffing, grunting, squeaking, coughing and words or phrases.

Possible strengths: - Excellent musical abilities.

- Memory capable of almost ‘total recall’.

- Excellent peripheral perception.

- Laser-like concentration.

People with Tourette Syndrome are not likely to do as well in the education system as neurotypicals and are less likely to go into higher education.

People with TS are likely to suffer environmental, cultural and economical problems. These problems could be prejudice from lecturers and other students, unsuitable learning environments and procedures not tailored for the neurologically diverse. Almost 50% of people with TS will also have ADHD.

Collaborate with student

In many cases the student will approach you and explain about their TS. It is a good idea to formulate a workable plan which takes into account the needs of the student and the course or module requirements.

Attention

People with TS are likely to have issues with attention in that they attend to everything, including posters, windows, noises from lights, clocks, heating etc. These people learn most effectively in environments with few visual and auditory distractions.

Tics

People with TS often tic when they are in situations that can draw unwanted attention. This is quite likely to happen in lectures, workshops and seminars. Tourettists have to tic, and should not be asked to suppress them or to be quiet, as suppression can often result in stronger and more aggressive tics.

Release time

Tourettists may want to leave the room if their tics get too intense. Don’t ask them where they are going as this may cause embarrassment in front of other students. Usually the absence will not be too long. However, if things get too bad the student may not feel able to return.

There is no widely accepted definition.

A useful definition for HE is ‘Dyscalculia is an inability to conceptualise numbers, number relationships (arithmetical facts) and the outcomes of numerical operations (estimating the answer to numerical problems before actually calculating)’ (Sharma, 1997 in: Pollak, 2009:126).

Estimates of prevalence in children: 3–8%. There are none for HE.

Students may have difficulty with: understanding and using mathematical concepts and relations; mathematical symbols or digits; mathematical operations.

They may also have difficulties in understanding time, money, direction and more abstract mathematical, symbolic and graphical representations together with severe mathematical anxiety: ‘the panic, helplessness, paralysis, and mental disorganization that arise among some people when they are required to solve a mathematical problem’ (Tobias & Weissbrod, 1980 in: Pollak, 2009:129).

HE issues:

- Choice of courses (pattern cutting, e.g., may be extremely stressful); arriving on time for classes because of difficulties with time and direction; completing work on time because of difficulty reading timetables/time management;

- Financial management leading to debt.

- All these may involve high anxiety.

- Social: dyscalculiac students may become isolated, avoiding social engagements involving money (shopping with fellow-students at the weekend, drinks in the bar) and time/place (meeting for coffee).

- Work placements and careers may be a source of anxiety.

Dyscalculia Screener At: http://dyscalculia-screener.co.uk/

Dysgraphia is defined as a difficulty in automatically remembering and mastering the sequence of muscle motor movements needed in writing letters or numbers. This difficulty is out of harmony with the person’s intelligence, regular teaching instruction, and (in most cases) the use of the pencil in non-learning tasks. It is neurologically based and exists in varying degrees, ranging from mild to moderate. It can be diagnosed, and it can be overcome if appropriate remedial strategies are taught well and conscientiously carried out. An adequate remedial programme generally works if applied on a daily basis. In many situations, it is relatively easy to plan appropriate compensations to be used as needed.

It is a processing problem that causes writing fatigue and interferes with communication in written form.

It usually exists with other symptoms of learning problems, particularly those connected with written language.

Dysgraphic students may mix upper and lower case letters or print in cursive letters. Size of letters may vary, and some letters may be incomplete.

A Tale of Two Workshops

Mike Rymer

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/microsites/creative-education/ce-newsletter-issue-1.jpg)

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-10-17-at-19.18.51-copy.jpg)

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-09-29-at-10.25.33-copy.jpg)

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-09-25-at-17.33.22.png)

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-09-25-at-17.18.05.png)

/prod01/channel_13/uca-creative-education/media/research-and-enterprise/nikolai/Screenshot-2025-09-25-at-16.55.02.png)